A rare photo of a Revolutionary War veteran [courtesy of findagrave.com]

William Sprague’s line of the family achieved prominence in the arts—from botanical illustration to poetry.

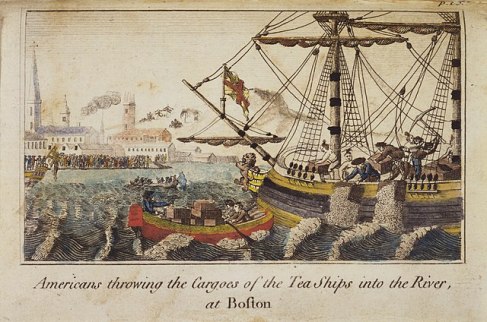

In this “Rev 250” period of commemoration of the War for Independence, I need to first mention that William’s great-great grandson, Samuel Sprague, born in Hingham in 1753, was a Revolutionary War Patriot who also participated in the Boston Tea Party, as discussed in a 2020 post on this blog. Samuel’s pension states that he crossed the Delaware with George Washington! (That tidbit is courtesy of the recently published book, Revolutionary War Patriots of Hingham, Ellen Stine Miller & Susan Garrett Wetzel, 2024, copies of which are available from the Hingham Historical Society.

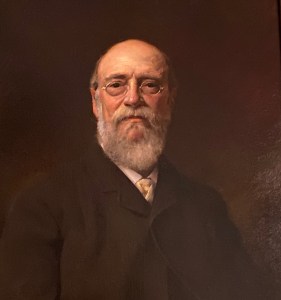

Portrait of Charles Sprague, the “Banker Poet,” by Matthew Sprague (Hingham Historical Society)

Charles Sprague (1791-1875) —Samuel’s son, Charles, was born in Boston, where his father Samuel earlier had relocated as an apprentice mason. Charles had success both in the banking business and as a poet and became well known as the “Banker Poet of Boston.” He is considered one of America’s earliest native-born poets. Some of his poems suggest an affinity for transcendentalism, a movement associated with Charles’ contemporaries Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, and Margaret Fuller, all of Massachusetts. One example of Charles’ poetry can be read here.

This portrait of Charles hangs in the hallway of the Hingham Historical Society’s General Benjamin Lincoln House (Charles’ granddaughter Helen Amelia Sprague married Lauriston Scaife, a Lincoln descendant). A modern notation on the back of the canvas attributes the painting to “Matthew Sprague”–another talented Sprague?

Charles James Sprague (1823-1903), like his father, was a banker and a poet but he left his mark in the field of botany. His portrait, looking very much like a respectable banker, also hangs in the Benjamin Lincoln House. It was painted by his nephew, Charles Sprague Pearce, a well-known painter of the 19th century.

Portrait of Charles James Sprague by Charles Sprague Pearce (Hingham Historical Society)

Charles James Sprague was known for his study and illustrations of lichens. More info about the Sprague Herbarium of Fungi can be found here.

Based on his scientific and literary contributions, Charles James Sprague was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1856.

Hosea Sprague (1779-1843) — A grandson of Isaac Sprague, Sr. (1709-1789) another Revolutionary War Patriot of Hingham, Hosea first trained as a printer in Boston. He then returned to Hingham where he worked as a bookseller and became known as a wood engraver.

A few of his engravings from the Hingham Historical Society archives are shown here.

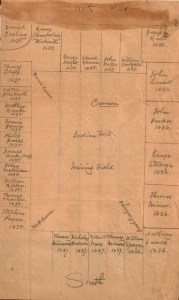

Hosea also was the compiler of The Genealogy of the Spragues in Hingham, published in 1828, an excerpt from  which is show here. The Hingham Library also has an original edition in its Sprague family archive. This genealogy is notable as it was published well-before the popularity of genealogies in the late 19th/early 20th century, following the 1876 U.S. centennial and the 1890 launch of the Daughters of the American Revolution, when charting colonial ancestry became quite popular.

which is show here. The Hingham Library also has an original edition in its Sprague family archive. This genealogy is notable as it was published well-before the popularity of genealogies in the late 19th/early 20th century, following the 1876 U.S. centennial and the 1890 launch of the Daughters of the American Revolution, when charting colonial ancestry became quite popular.

In the 1840s, Hosea published several issues of a periodical of his observations about life, history, and weather: “Hosea Sprague’s Chronicle.” In an October 18, 1888, feature story, published in the Hingham Journal, Hingham’s Luther Stephenson (a Civil War general, who had both maternal and paternal Sprague grandmothers) wrote about his cousin Hosea: “He had great respect for the first settlers of Hingham, and spent much time in deciphering and copying in his bold hand the early records of the town…”

Isaac Sprague (1811-1895)—A great grandson of Isaac the Revolutionary War Patriot, Isaac was born in Hingham. He became an Artist Assistant to the well-known illustrator John James Audubon, joining Audubon’s expedition to Montana in 1843. Isaac then began his successful career in Cambridge as a botanical illustrator, working with influential botanist Asa Gray and others. In recognition of Isaac’s Hingham roots, the Hingham Heritage Museum treasures its collection of several of Isaac’s beautiful artworks and the Society sponsored an exhibit of his work in 2016.

Here are some of the prints in our collection:

- Aesculus glabra Ohio Buckeye

- Gymnocladus Canadensis / Kentucky Coffee

- Azalea Nudiflora, L. / Purple Azalea

Isaac’s work has been the subject of two posts on this blog, —in 2016 and 2017:

In addition to poets and artists, the William Sprague line includes skilled craftsmen known as coopers—artisans in woodenware-making including boxes, buckets, and wooden toys, during the long period when Hingham was known to many as “Bucket Town.” This history is documented and beautifully illustrated in the book Bucket Town, Woodenware and Wooden Toys of Hingham, Massachusetts, 1635-1945, written by Derin T. Bray and published by the town’s Hingham Historic Commission in 2014.

In 2014-15, Old Sturbridge Village featured an exhibit titled “Bucket Town: Four Centuries of Toy-Making and Coopering in Hingham.” The Hingham Heritage Museum’s inaugural exhibition in 2017 was Boxes, Buckets, and Toys: the Craftsmen of Hingham.”

In 2014-15, Old Sturbridge Village featured an exhibit titled “Bucket Town: Four Centuries of Toy-Making and Coopering in Hingham.” The Hingham Heritage Museum’s inaugural exhibition in 2017 was Boxes, Buckets, and Toys: the Craftsmen of Hingham.”

Among the Hingham Sprague family members who were coopers/ woodenware makers are:

- Isaac Sprague, Sr. (1709-1789), the Revolutionary War Patriot, by trade a set-work (or bucket/barrel making) cooper; his son Isaac (1743-1800) also a set-work cooper; and Isaac Sprague, Jr.’s sons Peter (1773-1859) and Isaac (1782-1826) both of whom were box coopers. Peter’s son, Peter (1801-1868) also worked as a box cooper.

- Amos Sprague (1747-1838) a box cooper; and his son Amos (1774-1830) also a box cooper.

- Blossom Sprague (1784-1860), a carriage painter who was also an award-winning maker of wooden toys.

- Reuben Sprague (1785-1852), whose son Reuben O. Sprague (1811-1898) used his woodworking skills as a stair builder with a shop in Boston.

- Adna Sprague (1790-1860) a box cooper who also served in town government as a Selectman.

- Bela Sprague (1804-1878), a brother of engraver Hosea, a “white cooper,” or maker of buckets, pails, and other household containers. Bela’s work is featured in the Bucket Town book. We have some examples of Bela’s work in our Hingham Historical Society collection, including this bail-handled pail and a small pail with a handle, known as a “piggin.”

- Bail-handled water pail, by Bela Sprague (Hingham Historical Society)

- Piggin by Bela Sprague (Hingham Historical Society)

- Samuel Sprague (1809-1882), cooper, whose son Samuel (1833-1900) was a stair builder; and

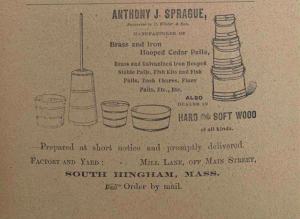

- Anthony J. Sprague (1855-1921), who ran the ad shown here for his woodenware business in the 1894 Hingham-Hull Directory. One of Anthony J. Sprague’s buckets is this firkin from the Historical Society’s collection.

- Firkin by A. J. Sprague (Hingham Historical Society)

- A. J. Sprague Woodenware Advertisement (1894 Hingham-Hull Directory)

Women of the 18th-mid 20th century were generally less recognized for their contributions to the arts, but we are fortunate to have examples of the illustrations of Lydia Sprague (1832-1907), a cousin of Isaac, and a daughter of box cooper Adna Sprague. Several examples of Lydia’s artistry are included in Joan Brancale’s two-part post on our blog from 2014:

Also in our collection are some wonderful samplers by Sprague women – created when they were in school.

- First, this sampler where nature and a structure (perhaps Derby Academy) are prominently featured, embroidered by Mary Sprague (1804-1871.) Mary was a daughter of Peter Sprague and Mary Whiton. She married Elijah Burr in 1828.

- Next, a genealogical sampler, which tells us in embroidery that the creator is a then 8-year-old Jane Sprague, who stitched it on May 1, 1820. As spelled out in stitches, Jane is a daughter of David Sprague and Mary Leavitt Gardner. Jane (1811-1878) married Thomas Cushing in 1836.

Before concluding this short visit with members of the William Sprague family line, a note about descendants who are an important part of the history of Rhode Island. William’s son William, born in Hingham in 1650, moved to Rhode Island around 1710. His grandson William, born in Cranston in 1795, started

a grist and sawmill in Cranston along the Pocasset River. The next generation built on that foundation, and much wealth was created in the process due to the success of A & W Sprague, which grew to become, for a time, the largest cotton textile manufacturer in the country. Their business success made members of this line quite wealthy and propelled some of the family into politics: two became Governors of Rhode Island in the 19th century. One of these, another William, born in 1830, also became a US Senator, and built an enormous estate in Narragansett, RI in the 1860s, named Canonchet.

Part 3 of this blog will focus on the descendants of Raph Sprague, older brother of Charlestown and Hingham settler William, — and this line’s lasting contributions to science, technology and related businesses.

Brothers Ralph (1599-1650), Richard (1605-1668) and William Sprague (1609-1675), were sons of Edward Sprague (1576-1614), who operated a fulling mill on the river Wey, in Upwey, located between Dorchester and Weymouth, in the county of Dorset, England. (Edward’s mill, shown here, no longer exists.) After their father’s death, the three brothers joined a party of colonists emigrating for the Mass Bay Company to settle what became Charlestown, Massachusetts. It is unclear if religion was part of the Sprague brothers’ motivation to leave England. They arrived in Salem in 1628, then soon traveled on to Charlestown.

Brothers Ralph (1599-1650), Richard (1605-1668) and William Sprague (1609-1675), were sons of Edward Sprague (1576-1614), who operated a fulling mill on the river Wey, in Upwey, located between Dorchester and Weymouth, in the county of Dorset, England. (Edward’s mill, shown here, no longer exists.) After their father’s death, the three brothers joined a party of colonists emigrating for the Mass Bay Company to settle what became Charlestown, Massachusetts. It is unclear if religion was part of the Sprague brothers’ motivation to leave England. They arrived in Salem in 1628, then soon traveled on to Charlestown.

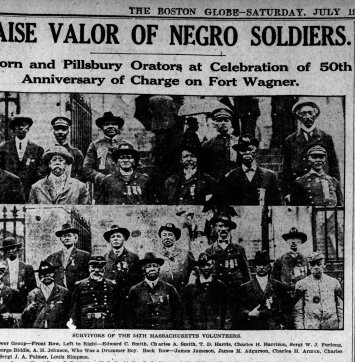

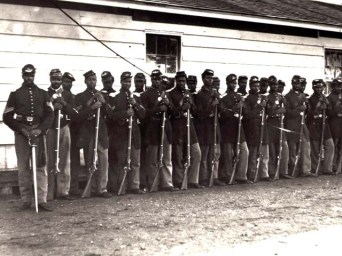

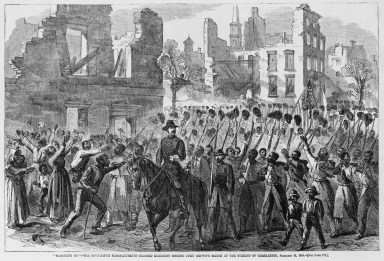

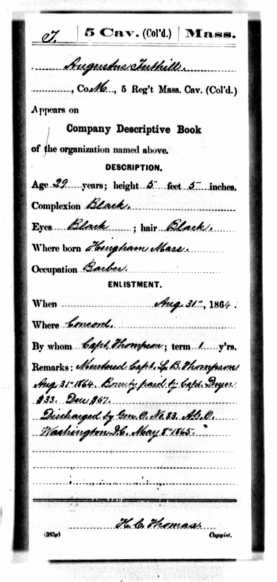

Champlin was mustered out with the rest of the regiment on August 20, 1865, at Mount Pleasant, South Carolina.

Champlin was mustered out with the rest of the regiment on August 20, 1865, at Mount Pleasant, South Carolina.

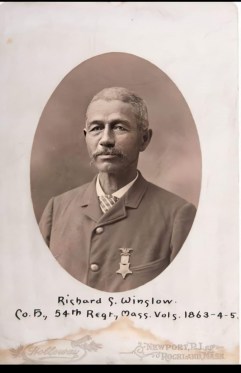

After the war, Winslow and his family lived in Hanover, where he died at age 73 in 1904. His obituary mentioned his service with the Mass. 54th , his later active involvement with Hanover and Plymouth GAR posts, and his membership in Hanover’s Methodist Church. Winslow is buried in the Hanover Center Cemetery.

After the war, Winslow and his family lived in Hanover, where he died at age 73 in 1904. His obituary mentioned his service with the Mass. 54th , his later active involvement with Hanover and Plymouth GAR posts, and his membership in Hanover’s Methodist Church. Winslow is buried in the Hanover Center Cemetery.

Meanwhile, as we celebrate

Meanwhile, as we celebrate

This wooden tub is from the Little Plain Engine, No. 1, nicknamed the “Precedent” because it was the first of what would ultimately be four such engines to be completed. It was manufactured by local craftsmen: Peter Sprague made the tub from cedar furnished by Thomas Fearing. The ironwork was by the local firm of Stephenson and Thomas.

This wooden tub is from the Little Plain Engine, No. 1, nicknamed the “Precedent” because it was the first of what would ultimately be four such engines to be completed. It was manufactured by local craftsmen: Peter Sprague made the tub from cedar furnished by Thomas Fearing. The ironwork was by the local firm of Stephenson and Thomas. This beautiful drop-front desk and bookcase, newly installed in the Kelly Gallery at the Hingham Heritage Museum at Old Derby Academy, was built for Martin Gay (1726-1807) and Ruth Atkins Gay (1736-1810) upon their marriage in 1765 by cabinetmaker Gibbs Atkins of Boston, Ruth’s brother.

This beautiful drop-front desk and bookcase, newly installed in the Kelly Gallery at the Hingham Heritage Museum at Old Derby Academy, was built for Martin Gay (1726-1807) and Ruth Atkins Gay (1736-1810) upon their marriage in 1765 by cabinetmaker Gibbs Atkins of Boston, Ruth’s brother. The birds’-eye view of Hingham Harbor, circa 1680, envisions Hingham as its earliest settlers found it, a heavily forested coastal village with a safe harbor and large tidal inlet called “Mill Pond.” The mural’s design concept, developed with

The birds’-eye view of Hingham Harbor, circa 1680, envisions Hingham as its earliest settlers found it, a heavily forested coastal village with a safe harbor and large tidal inlet called “Mill Pond.” The mural’s design concept, developed with  The focus is on early North Street, later the route by which woodenware from village workshops of Hingham Centre and Hersey Street made their way down the harbor where ships awaited to carry them worldwide. The twilight setting was inspired by exhibit writer Carrie Brown’s description of candlelit homes in a world fueled and maintained by wood.

The focus is on early North Street, later the route by which woodenware from village workshops of Hingham Centre and Hersey Street made their way down the harbor where ships awaited to carry them worldwide. The twilight setting was inspired by exhibit writer Carrie Brown’s description of candlelit homes in a world fueled and maintained by wood. suggested the steeple of Old Ship Church (not yet built) to help locate the site of an earlier meetinghouse on Main Street. At the harbor a single wharf, likely located at the mouth of Mill Pond, suggests the beginning of Hingham’s commercial harbor. In later years, Hingham harbor’s many wharves were key to the success transporting goods produced by local tradesmen to Boston and beyond.

suggested the steeple of Old Ship Church (not yet built) to help locate the site of an earlier meetinghouse on Main Street. At the harbor a single wharf, likely located at the mouth of Mill Pond, suggests the beginning of Hingham’s commercial harbor. In later years, Hingham harbor’s many wharves were key to the success transporting goods produced by local tradesmen to Boston and beyond. The viewer may be surprised at the prominence of Mill Pond—how it extends in the distance to what is now Home Meadows. This once broad expanse of water carried early settler Peter Hobart and company to their landing point at the foot of Ship Street at North Street. Mill Pond, flushed by tidal waters and fed by the Town Brook, is, alas, no longer. In the late 1940s it was “paved over for a parking lot” along Station Street and the historic brook sent underground. The vestige of Mill Pond’s shoreline still remains, along the rear of old buildings lining the south side of North Street.

The viewer may be surprised at the prominence of Mill Pond—how it extends in the distance to what is now Home Meadows. This once broad expanse of water carried early settler Peter Hobart and company to their landing point at the foot of Ship Street at North Street. Mill Pond, flushed by tidal waters and fed by the Town Brook, is, alas, no longer. In the late 1940s it was “paved over for a parking lot” along Station Street and the historic brook sent underground. The vestige of Mill Pond’s shoreline still remains, along the rear of old buildings lining the south side of North Street. Research was important to surmise how Hingham Harbor may have first appeared to arriving settlers. I found no local 17th century drawings or paintings on which to base the design. Instead I used a variety of sources to help me understand what might be a plausible view. My research included:

Research was important to surmise how Hingham Harbor may have first appeared to arriving settlers. I found no local 17th century drawings or paintings on which to base the design. Instead I used a variety of sources to help me understand what might be a plausible view. My research included: