Each year, the Hingham Historical Society awards its W. Bradford Sprout, Jr., Architectural Award in recognition of a notable project involving the rehabilitation, restoration or preservation of an historic structure or property in the town of Hingham. This past spring, at a “virtual” Annual Meeting of the Society, the award was presented to the Trustees of High Street Cemetery for their restoration of Whiting Memorial Chapel.

Albert Turner Whiting in front of the newly constructed chapel, 1905.

Albert Turner Whiting commission this stone chapel, completed in 1905, in memory of his parents, Albert and Sarah Fearing Whiting, and his wife Harriet E. (Warren) Whiting, who died in January 1905, while the chapel was under construction. Whiting had already lost his only child, Helen, in 1891. All are buried in High Street Cemetery.

Harriet Whiting Memorial Window.

J. Sumner Fowler, a Hingham resident and architect, designed Whiting Chapel. (He, too, is buried in High Street Cemetery.) The chapel is in the Gothic Revival style, popular nationally–think college campuses–although there are no other examples of the stye in Hingham. The chapel was constructed of Weymouth seam-faced granite with Indiana limestone trimming. It has a copper roof and double oak doors.

The interior features oak paneled walls and copious stained glass, including an ornate window in the apse, in memory of Whiting’s wife, Harriet E. (Warren) Whiting, who died in early 1905.

The Whitings (sometimes also Whitons) were a large and important family in South Hingham. Albert Whiting (Albert Turner’s father) built an Italianate Revival house that once stood at 1194 Main Street, just north of Queen Anne Corner.

Albert Whiting’s House at 1194 Main Street.

The elder Albert Whiting was a master mason, who was superintendent of stone work on many large public projects, including the Charlestown Navy Yard dry docks; Castle Island in South Boston; Fort Independence in Hull; and industrial canals for the Lowell Lock and Canal Co. His son, Albert Turner Whiting, had a peripatetic youth, as his father’s trade required the family to move to these large building sites. It is no wonder, then, that when the younger Albert came to commission a chapel in his parents’ honor, the result was one of Hingham’s only stone buildings.

Fowler, the architect, designed many well-known Hingham and South Shore buildings, including the former Town Offices at 14 Main Street and Ames Chapel in Hingham Cemetery, also recently restored. That chapel could not be more different, though, having been designed in 1887 in the then-popular, richly ornamented Queen Anne style.

High Street Cemetery is the oldest cemetery in South Hingham. Its earliest extant headstone dates from 1688. Through the mid-19th century, it was the responsibility of Hingham’s Second Parish. It passed into private hands and was incorporated in 1855.

Restoration worked focused on interior and exterior wall repair due to leaks; floor repair; pew cleaning; and the repair and restoration of stained glass. The oak doors and paneling were stripped and restained and an HVAC system was installed. This work, performed by Ben Wilcox and Wilcox Construction, was funded by the Trustees’ endowment and a grant from the CPC. The Trustees sought to restore the building for use for private events, and, as restored it comfortably seats 80.

The Trustees’ work makes a significant and beautiful building available to the Town, and for that we were pleased to honor the Trustees with the Sprout award. Although outside of the public eye, owing to social distancing measures, the Trustees were awarded a plaque commemorating the award. Special thanks to Aisling Gallery, which generously donated framing services, and Susan Kilmartin, for sharing her calligraphy skills.

Whiting Memorial Chapel in High Street Cemetery, 2019.

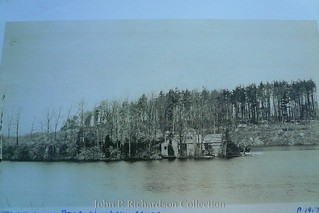

Back in 1946 there was a bit of a housing shortage. Hingham dentist Ross Vroom bought a two-story Garrison colonial house on Gallops Island and had it placed on a barge and floated over to World’s End. He had a cellar dug at 22 Seal Cove Road, and the house still sits there today.

Back in 1946 there was a bit of a housing shortage. Hingham dentist Ross Vroom bought a two-story Garrison colonial house on Gallops Island and had it placed on a barge and floated over to World’s End. He had a cellar dug at 22 Seal Cove Road, and the house still sits there today.