A rare photo of a Revolutionary War veteran [courtesy of findagrave.com]

William Sprague’s line of the family achieved prominence in the arts—from botanical illustration to poetry.

In this “Rev 250” period of commemoration of the War for Independence, I need to first mention that William’s great-great grandson, Samuel Sprague, born in Hingham in 1753, was a Revolutionary War Patriot who also participated in the Boston Tea Party, as discussed in a 2020 post on this blog. Samuel’s pension states that he crossed the Delaware with George Washington! (That tidbit is courtesy of the recently published book, Revolutionary War Patriots of Hingham, Ellen Stine Miller & Susan Garrett Wetzel, 2024, copies of which are available from the Hingham Historical Society.

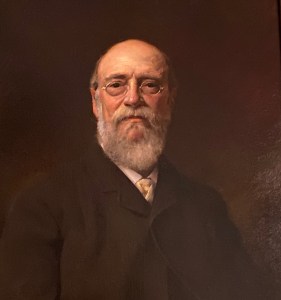

Portrait of Charles Sprague, the “Banker Poet,” by Matthew Sprague (Hingham Historical Society)

Charles Sprague (1791-1875) —Samuel’s son, Charles, was born in Boston, where his father Samuel earlier had relocated as an apprentice mason. Charles had success both in the banking business and as a poet and became well known as the “Banker Poet of Boston.” He is considered one of America’s earliest native-born poets. Some of his poems suggest an affinity for transcendentalism, a movement associated with Charles’ contemporaries Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, and Margaret Fuller, all of Massachusetts. One example of Charles’ poetry can be read here.

This portrait of Charles hangs in the hallway of the Hingham Historical Society’s General Benjamin Lincoln House (Charles’ granddaughter Helen Amelia Sprague married Lauriston Scaife, a Lincoln descendant). A modern notation on the back of the canvas attributes the painting to “Matthew Sprague”–another talented Sprague?

Charles James Sprague (1823-1903), like his father, was a banker and a poet but he left his mark in the field of botany. His portrait, looking very much like a respectable banker, also hangs in the Benjamin Lincoln House. It was painted by his nephew, Charles Sprague Pearce, a well-known painter of the 19th century.

Portrait of Charles James Sprague by Charles Sprague Pearce (Hingham Historical Society)

Charles James Sprague was known for his study and illustrations of lichens. More info about the Sprague Herbarium of Fungi can be found here.

Based on his scientific and literary contributions, Charles James Sprague was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1856.

Hosea Sprague (1779-1843) — A grandson of Isaac Sprague, Sr. (1709-1789) another Revolutionary War Patriot of Hingham, Hosea first trained as a printer in Boston. He then returned to Hingham where he worked as a bookseller and became known as a wood engraver.

A few of his engravings from the Hingham Historical Society archives are shown here.

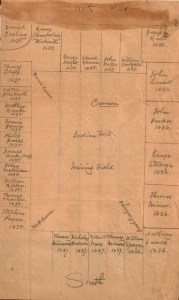

Hosea also was the compiler of The Genealogy of the Spragues in Hingham, published in 1828, an excerpt from  which is show here. The Hingham Library also has an original edition in its Sprague family archive. This genealogy is notable as it was published well-before the popularity of genealogies in the late 19th/early 20th century, following the 1876 U.S. centennial and the 1890 launch of the Daughters of the American Revolution, when charting colonial ancestry became quite popular.

which is show here. The Hingham Library also has an original edition in its Sprague family archive. This genealogy is notable as it was published well-before the popularity of genealogies in the late 19th/early 20th century, following the 1876 U.S. centennial and the 1890 launch of the Daughters of the American Revolution, when charting colonial ancestry became quite popular.

In the 1840s, Hosea published several issues of a periodical of his observations about life, history, and weather: “Hosea Sprague’s Chronicle.” In an October 18, 1888, feature story, published in the Hingham Journal, Hingham’s Luther Stephenson (a Civil War general, who had both maternal and paternal Sprague grandmothers) wrote about his cousin Hosea: “He had great respect for the first settlers of Hingham, and spent much time in deciphering and copying in his bold hand the early records of the town…”

Isaac Sprague (1811-1895)—A great grandson of Isaac the Revolutionary War Patriot, Isaac was born in Hingham. He became an Artist Assistant to the well-known illustrator John James Audubon, joining Audubon’s expedition to Montana in 1843. Isaac then began his successful career in Cambridge as a botanical illustrator, working with influential botanist Asa Gray and others. In recognition of Isaac’s Hingham roots, the Hingham Heritage Museum treasures its collection of several of Isaac’s beautiful artworks and the Society sponsored an exhibit of his work in 2016.

Here are some of the prints in our collection:

- Aesculus glabra Ohio Buckeye

- Gymnocladus Canadensis / Kentucky Coffee

- Azalea Nudiflora, L. / Purple Azalea

Isaac’s work has been the subject of two posts on this blog, —in 2016 and 2017:

In addition to poets and artists, the William Sprague line includes skilled craftsmen known as coopers—artisans in woodenware-making including boxes, buckets, and wooden toys, during the long period when Hingham was known to many as “Bucket Town.” This history is documented and beautifully illustrated in the book Bucket Town, Woodenware and Wooden Toys of Hingham, Massachusetts, 1635-1945, written by Derin T. Bray and published by the town’s Hingham Historic Commission in 2014.

In 2014-15, Old Sturbridge Village featured an exhibit titled “Bucket Town: Four Centuries of Toy-Making and Coopering in Hingham.” The Hingham Heritage Museum’s inaugural exhibition in 2017 was Boxes, Buckets, and Toys: the Craftsmen of Hingham.”

In 2014-15, Old Sturbridge Village featured an exhibit titled “Bucket Town: Four Centuries of Toy-Making and Coopering in Hingham.” The Hingham Heritage Museum’s inaugural exhibition in 2017 was Boxes, Buckets, and Toys: the Craftsmen of Hingham.”

Among the Hingham Sprague family members who were coopers/ woodenware makers are:

- Isaac Sprague, Sr. (1709-1789), the Revolutionary War Patriot, by trade a set-work (or bucket/barrel making) cooper; his son Isaac (1743-1800) also a set-work cooper; and Isaac Sprague, Jr.’s sons Peter (1773-1859) and Isaac (1782-1826) both of whom were box coopers. Peter’s son, Peter (1801-1868) also worked as a box cooper.

- Amos Sprague (1747-1838) a box cooper; and his son Amos (1774-1830) also a box cooper.

- Blossom Sprague (1784-1860), a carriage painter who was also an award-winning maker of wooden toys.

- Reuben Sprague (1785-1852), whose son Reuben O. Sprague (1811-1898) used his woodworking skills as a stair builder with a shop in Boston.

- Adna Sprague (1790-1860) a box cooper who also served in town government as a Selectman.

- Bela Sprague (1804-1878), a brother of engraver Hosea, a “white cooper,” or maker of buckets, pails, and other household containers. Bela’s work is featured in the Bucket Town book. We have some examples of Bela’s work in our Hingham Historical Society collection, including this bail-handled pail and a small pail with a handle, known as a “piggin.”

- Bail-handled water pail, by Bela Sprague (Hingham Historical Society)

- Piggin by Bela Sprague (Hingham Historical Society)

- Samuel Sprague (1809-1882), cooper, whose son Samuel (1833-1900) was a stair builder; and

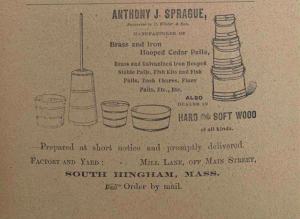

- Anthony J. Sprague (1855-1921), who ran the ad shown here for his woodenware business in the 1894 Hingham-Hull Directory. One of Anthony J. Sprague’s buckets is this firkin from the Historical Society’s collection.

- Firkin by A. J. Sprague (Hingham Historical Society)

- A. J. Sprague Woodenware Advertisement (1894 Hingham-Hull Directory)

Women of the 18th-mid 20th century were generally less recognized for their contributions to the arts, but we are fortunate to have examples of the illustrations of Lydia Sprague (1832-1907), a cousin of Isaac, and a daughter of box cooper Adna Sprague. Several examples of Lydia’s artistry are included in Joan Brancale’s two-part post on our blog from 2014:

Also in our collection are some wonderful samplers by Sprague women – created when they were in school.

- First, this sampler where nature and a structure (perhaps Derby Academy) are prominently featured, embroidered by Mary Sprague (1804-1871.) Mary was a daughter of Peter Sprague and Mary Whiton. She married Elijah Burr in 1828.

- Next, a genealogical sampler, which tells us in embroidery that the creator is a then 8-year-old Jane Sprague, who stitched it on May 1, 1820. As spelled out in stitches, Jane is a daughter of David Sprague and Mary Leavitt Gardner. Jane (1811-1878) married Thomas Cushing in 1836.

Before concluding this short visit with members of the William Sprague family line, a note about descendants who are an important part of the history of Rhode Island. William’s son William, born in Hingham in 1650, moved to Rhode Island around 1710. His grandson William, born in Cranston in 1795, started

a grist and sawmill in Cranston along the Pocasset River. The next generation built on that foundation, and much wealth was created in the process due to the success of A & W Sprague, which grew to become, for a time, the largest cotton textile manufacturer in the country. Their business success made members of this line quite wealthy and propelled some of the family into politics: two became Governors of Rhode Island in the 19th century. One of these, another William, born in 1830, also became a US Senator, and built an enormous estate in Narragansett, RI in the 1860s, named Canonchet.

Part 3 of this blog will focus on the descendants of Raph Sprague, older brother of Charlestown and Hingham settler William, — and this line’s lasting contributions to science, technology and related businesses.

Brothers Ralph (1599-1650), Richard (1605-1668) and William Sprague (1609-1675), were sons of Edward Sprague (1576-1614), who operated a fulling mill on the river Wey, in Upwey, located between Dorchester and Weymouth, in the county of Dorset, England. (Edward’s mill, shown here, no longer exists.) After their father’s death, the three brothers joined a party of colonists emigrating for the Mass Bay Company to settle what became Charlestown, Massachusetts. It is unclear if religion was part of the Sprague brothers’ motivation to leave England. They arrived in Salem in 1628, then soon traveled on to Charlestown.

Brothers Ralph (1599-1650), Richard (1605-1668) and William Sprague (1609-1675), were sons of Edward Sprague (1576-1614), who operated a fulling mill on the river Wey, in Upwey, located between Dorchester and Weymouth, in the county of Dorset, England. (Edward’s mill, shown here, no longer exists.) After their father’s death, the three brothers joined a party of colonists emigrating for the Mass Bay Company to settle what became Charlestown, Massachusetts. It is unclear if religion was part of the Sprague brothers’ motivation to leave England. They arrived in Salem in 1628, then soon traveled on to Charlestown.

The triplets were given family names and not only did they all survive at a time when infant and child mortality was high, they all lived long lives. Hubbard and Polly lived to 78 and Lincoln to 80. This was so unusual that when, in 1889, the Burlington Weekly Free Press ran an article titled “Long-lived Triplets,” which featured three sets of New England triplets, the Litchfields were included.

The triplets were given family names and not only did they all survive at a time when infant and child mortality was high, they all lived long lives. Hubbard and Polly lived to 78 and Lincoln to 80. This was so unusual that when, in 1889, the Burlington Weekly Free Press ran an article titled “Long-lived Triplets,” which featured three sets of New England triplets, the Litchfields were included.

Jr., who in 1900 had his own family home on Lincoln Street, was a prominent attorney, and in 1902 would be elected as state representative from the 3rd district. Over on Green Street, Aunt Judith must have been quite proud, although in 1902, as a woman, she would not yet have had the right to vote.

Jr., who in 1900 had his own family home on Lincoln Street, was a prominent attorney, and in 1902 would be elected as state representative from the 3rd district. Over on Green Street, Aunt Judith must have been quite proud, although in 1902, as a woman, she would not yet have had the right to vote.

But Green Street’s location near the harbor gave its residents convenient access to work related to the coal and wood fuel-supply dealers, lumber wharves, and other harbor-related businesses. For many, this proximity to businesses needing carting and other hauling and loading services created jobs as teamsters, or as hostlers. Teamsters living on Green Street in 1900 included the recently married Cornelius Ryan, 31, and William Welch, 33 and married with young children.

But Green Street’s location near the harbor gave its residents convenient access to work related to the coal and wood fuel-supply dealers, lumber wharves, and other harbor-related businesses. For many, this proximity to businesses needing carting and other hauling and loading services created jobs as teamsters, or as hostlers. Teamsters living on Green Street in 1900 included the recently married Cornelius Ryan, 31, and William Welch, 33 and married with young children.

the Morrsisseys, 1900 was just seven years since the tragic loss of three of their young children to scarlet fever. The children’s young lives are memorialized on the family headstone at St. Paul’s Cemetery. Both Thomas and Mary were born in Irish immigrant households in Hingham. Thomas grew up on Elm Street. Mary’s parents earlier had a home on Green Street but after her dad’s death, her mother Ellen Crehan lived with her youngest daughter Catherine’s family here.

the Morrsisseys, 1900 was just seven years since the tragic loss of three of their young children to scarlet fever. The children’s young lives are memorialized on the family headstone at St. Paul’s Cemetery. Both Thomas and Mary were born in Irish immigrant households in Hingham. Thomas grew up on Elm Street. Mary’s parents earlier had a home on Green Street but after her dad’s death, her mother Ellen Crehan lived with her youngest daughter Catherine’s family here.

boarder, Michael Wallace, also a railroad worker. Taking in boarders was a common practice in the Irish community here, both to assist newer immigrants and to provide added income for the household. The children in the Kelly household as of 1900 included four daughters and two sons, all under ten years old. Another daughter would be born in 1901. Three of the “Kelly girls” of Green Street would, years later, be among the first women in Hingham to

boarder, Michael Wallace, also a railroad worker. Taking in boarders was a common practice in the Irish community here, both to assist newer immigrants and to provide added income for the household. The children in the Kelly household as of 1900 included four daughters and two sons, all under ten years old. Another daughter would be born in 1901. Three of the “Kelly girls” of Green Street would, years later, be among the first women in Hingham to

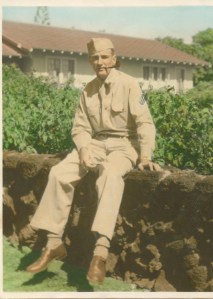

Hingham native Oliver L. (“Morg”) Ferris (1918-1985) served in the Army Air Corps as an airplane mechanic stationed in Hawaii and Guam, achieving the rank of Sergeant. He was a married man when he entered the service; while he was abroad, his wife, Margaret (“Rita”) Ferris, lived with her parents, the Scanlans, in Dorchester. For Christmas 1944, Morg sent Rita and her parents an Army Air Corps Christmas card which he signed on the front: “With all my love, Morg.” The card, postmarked December 9, 1944, shows aircraft in formation flying out of clouds towards what looks like a Christmas star. Between border decorations of palm trees and holiday wreaths at the top and bottom, it includes an inspirational, mission-driven message: “That It Might Shine On.”

Hingham native Oliver L. (“Morg”) Ferris (1918-1985) served in the Army Air Corps as an airplane mechanic stationed in Hawaii and Guam, achieving the rank of Sergeant. He was a married man when he entered the service; while he was abroad, his wife, Margaret (“Rita”) Ferris, lived with her parents, the Scanlans, in Dorchester. For Christmas 1944, Morg sent Rita and her parents an Army Air Corps Christmas card which he signed on the front: “With all my love, Morg.” The card, postmarked December 9, 1944, shows aircraft in formation flying out of clouds towards what looks like a Christmas star. Between border decorations of palm trees and holiday wreaths at the top and bottom, it includes an inspirational, mission-driven message: “That It Might Shine On.” Air Corps, but his choice of Christmas card could not have been more different! Richard served in the National Guard from 1939 to 1940 and, from 1941 to 1945, with the Army Air Corps as a member of the 3rd Bomber Group, which took the nickname “The Grim Reapers.”

Air Corps, but his choice of Christmas card could not have been more different! Richard served in the National Guard from 1939 to 1940 and, from 1941 to 1945, with the Army Air Corps as a member of the 3rd Bomber Group, which took the nickname “The Grim Reapers.” While the card is undated and bears no postmark, the context suggests it may have been sent for Christmas 1943, when the Third Bomber Group was indeed very “busy” with aerial bombing of New Guinea, as the allies fought a lengthy campaign to win New Guinea, which had been invaded by the Japanese in 1942. (Shown here: the 3rd Bomber Group attacks Japanese ships in Simpson Harbor, New Guinea, Nov. 2, 1943. Photo courtesy of the

While the card is undated and bears no postmark, the context suggests it may have been sent for Christmas 1943, when the Third Bomber Group was indeed very “busy” with aerial bombing of New Guinea, as the allies fought a lengthy campaign to win New Guinea, which had been invaded by the Japanese in 1942. (Shown here: the 3rd Bomber Group attacks Japanese ships in Simpson Harbor, New Guinea, Nov. 2, 1943. Photo courtesy of the  undated card, sent to Morg and Rita, riffs on exotic travel posters of the day, featuring a four-color picture of a G.I. drinking from a coconut shell or wooden bowl offered by a native woman, while a native man operates a well nearby. “All’s Well in the Philippines,” the card reassures the recipient (albeit with a very bad pun). Inside, Ed has carefully handwritten the names of various cities in the Philippines in a style suggestive of steamer trunk labels and wrote:

undated card, sent to Morg and Rita, riffs on exotic travel posters of the day, featuring a four-color picture of a G.I. drinking from a coconut shell or wooden bowl offered by a native woman, while a native man operates a well nearby. “All’s Well in the Philippines,” the card reassures the recipient (albeit with a very bad pun). Inside, Ed has carefully handwritten the names of various cities in the Philippines in a style suggestive of steamer trunk labels and wrote:

After recuperating from a wound suffered during the

After recuperating from a wound suffered during the

What the letter doesn’t tell us is that Adna was only 44 years old when he died. It doesn’t say how his wife and children learned of his death. Knowing he was buried the day he died, we understand that he was in the ground before most people knew he was dead. We see that immediately following his death a group of friends or co-workers carried his body from Charlestown to Hingham by sailboat. We know the news was rushed to Hingham Centre, and that the Fearing Burrs opened their home for an unexpected funeral. We realize that, in a matter of hours, a coffin was acquired, a gravedigger found, and a minister fetched. We are left to imagine the ripples of grief that spread across the villages and towns as friends and family heard the news.

What the letter doesn’t tell us is that Adna was only 44 years old when he died. It doesn’t say how his wife and children learned of his death. Knowing he was buried the day he died, we understand that he was in the ground before most people knew he was dead. We see that immediately following his death a group of friends or co-workers carried his body from Charlestown to Hingham by sailboat. We know the news was rushed to Hingham Centre, and that the Fearing Burrs opened their home for an unexpected funeral. We realize that, in a matter of hours, a coffin was acquired, a gravedigger found, and a minister fetched. We are left to imagine the ripples of grief that spread across the villages and towns as friends and family heard the news. In the 1840s Sprague left Hingham and moved to Cambridge, where he worked with influential botanists, including

In the 1840s Sprague left Hingham and moved to Cambridge, where he worked with influential botanists, including  Sprague first produced the illustrations for Asa Gray’s 1845 Lowell lectures at Harvard and then assisted with several comprehensive botanical volumes over the course of the 1840s and 1850s. His illustrations were scientific tools first and aesthetic objects second: Sprague considered himself to be a naturalist or delineator rather than describing himself as an artist. In the preface to his 1848 work

Sprague first produced the illustrations for Asa Gray’s 1845 Lowell lectures at Harvard and then assisted with several comprehensive botanical volumes over the course of the 1840s and 1850s. His illustrations were scientific tools first and aesthetic objects second: Sprague considered himself to be a naturalist or delineator rather than describing himself as an artist. In the preface to his 1848 work  On August 14, 1862,

On August 14, 1862,

Although Lincoln disappointed Sumner by moving deliberately toward introducing uniformed black soldiers into the Union Army, his administration responded positively when, in January 1863, Massachusetts’ abolitionist war Governor, Hingham’s own

Although Lincoln disappointed Sumner by moving deliberately toward introducing uniformed black soldiers into the Union Army, his administration responded positively when, in January 1863, Massachusetts’ abolitionist war Governor, Hingham’s own