A Review of Meg Ferris Kenagy’s Book The House on School Street: Eight Generations. Two Hundred and Four Years. One Family.

Not many people can say their family lived in the same house for eight generations, and even fewer strive to uncover the lives of these ancestors. Meg Ferris Kenagy is one of these rare individuals as she dives head first into this challenge and presents her discoveries in her book The House on School Street: Eight Fenerations. Two Hundred and Four years. One Family. Kenagy brings the history of her family’s house to life through numerous stories about her ancestors. We experience their lives and deaths, births and marriages, and the resulting joys and heartaches that accompany each event.

Martha Sprague Litchfield, left, and Sarah Trowbridge Litchfield. Circa 1890. Photo courtesy of the Hingham Historical Society.

Kenagy’s vivid descriptions of her family, the house, and Hingham make it feel like she is sitting down with us and flipping through pages of a photo album while sharing her family’s story. We see Colonel Charles Cushing building the house in 1785 after fighting in the Revolutionary War, and we watch subsequent generations move into and out of the family home. We learn of the successes and struggles of the family as they find ways to make a living in a changing world. As Kenagy shifts the narrative’s focus to each owner chapter after chapter, she recognizes the unique relationship each family member had with the house on School Street. She successfully sees the house through each of their eyes.

Although Kenagy admits there are gaps in her family’s story that research cannot fill, she does not let this obstacle frustrate her. Instead, Kenagy embraces what she does not know and proposes answers to the questions she cannot answer. By doing so, she becomes more attuned to the motivations, fears, and struggles of her ancestors. When Kenagy does know the answer to certain questions, she occasionally quotes letters and other sources to add another layer to her family’s story.

A large barn can be seen to the left of the house in this 1889 photo. A carriage house is to the right of the house. Photo courtesy of the Hingham Historical Society.

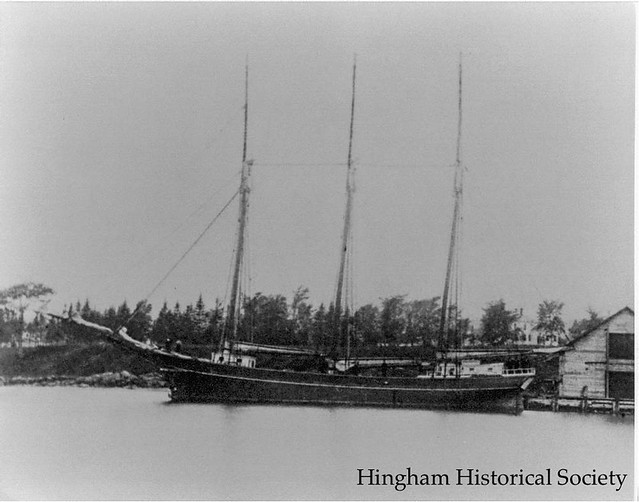

While this book presents the story about eight generations of a family, it also provides an overview of the history of Hingham. Through Kenagy’s detailed descriptions, we see Hingham’s transformation from a small village to a bustling wartime shipyard. Selected quotes from sources like the History of the Town of Hingham, Massachusetts and the Hingham Journal bring the town’s history to life. By acknowledging the history of the town, we can clearly recognize the family’s influence on Hingham’s community.

You can sense writing this book was a deeply personal experience for Kenagy. Not only does it document how she confirms family stories, but also how she uncovers family secrets. We are excited to learn more about Meg Kenagy’s experience writing this book and researching her family’s history when she comes to the Hingham Heritage Museum at Old Derby for a talk and book signing on Saturday, October 27, 2018 at 3:00pm. Please join us!

This wooden tub is from the Little Plain Engine, No. 1, nicknamed the “Precedent” because it was the first of what would ultimately be four such engines to be completed. It was manufactured by local craftsmen: Peter Sprague made the tub from cedar furnished by Thomas Fearing. The ironwork was by the local firm of Stephenson and Thomas.

This wooden tub is from the Little Plain Engine, No. 1, nicknamed the “Precedent” because it was the first of what would ultimately be four such engines to be completed. It was manufactured by local craftsmen: Peter Sprague made the tub from cedar furnished by Thomas Fearing. The ironwork was by the local firm of Stephenson and Thomas.

A steam-powered, side wheel vessel, the Mayflower was the lone survivor of a wharf fire that destroyed 4 other Nantasket Steamboat passenger boats in 1929. After over 40 years, she was taken out of service and while grounded on Nantasket Beach, lived nearly 40 more years as the nightclub “Showboat”. Frederick Lane was also the owner of the Pear Tree Hill Dairy, purveyors of high grade milk, cream and butter located on Main St. in Hingham. Lane passed away in Warner, New Hampshire in July of 1943. He is buried in Hingham Cemetery.

A steam-powered, side wheel vessel, the Mayflower was the lone survivor of a wharf fire that destroyed 4 other Nantasket Steamboat passenger boats in 1929. After over 40 years, she was taken out of service and while grounded on Nantasket Beach, lived nearly 40 more years as the nightclub “Showboat”. Frederick Lane was also the owner of the Pear Tree Hill Dairy, purveyors of high grade milk, cream and butter located on Main St. in Hingham. Lane passed away in Warner, New Hampshire in July of 1943. He is buried in Hingham Cemetery. On September 18, 1933, under the headline, “Railroad Tracks Washed Out During Storm Last Sunday,” the

On September 18, 1933, under the headline, “Railroad Tracks Washed Out During Storm Last Sunday,” the  The storm that took out the railroad embankment is not as locally famous as the

The storm that took out the railroad embankment is not as locally famous as the

This beautiful drop-front desk and bookcase, newly installed in the Kelly Gallery at the Hingham Heritage Museum at Old Derby Academy, was built for Martin Gay (1726-1807) and Ruth Atkins Gay (1736-1810) upon their marriage in 1765 by cabinetmaker Gibbs Atkins of Boston, Ruth’s brother.

This beautiful drop-front desk and bookcase, newly installed in the Kelly Gallery at the Hingham Heritage Museum at Old Derby Academy, was built for Martin Gay (1726-1807) and Ruth Atkins Gay (1736-1810) upon their marriage in 1765 by cabinetmaker Gibbs Atkins of Boston, Ruth’s brother. The birds’-eye view of Hingham Harbor, circa 1680, envisions Hingham as its earliest settlers found it, a heavily forested coastal village with a safe harbor and large tidal inlet called “Mill Pond.” The mural’s design concept, developed with

The birds’-eye view of Hingham Harbor, circa 1680, envisions Hingham as its earliest settlers found it, a heavily forested coastal village with a safe harbor and large tidal inlet called “Mill Pond.” The mural’s design concept, developed with  The focus is on early North Street, later the route by which woodenware from village workshops of Hingham Centre and Hersey Street made their way down the harbor where ships awaited to carry them worldwide. The twilight setting was inspired by exhibit writer Carrie Brown’s description of candlelit homes in a world fueled and maintained by wood.

The focus is on early North Street, later the route by which woodenware from village workshops of Hingham Centre and Hersey Street made their way down the harbor where ships awaited to carry them worldwide. The twilight setting was inspired by exhibit writer Carrie Brown’s description of candlelit homes in a world fueled and maintained by wood. suggested the steeple of Old Ship Church (not yet built) to help locate the site of an earlier meetinghouse on Main Street. At the harbor a single wharf, likely located at the mouth of Mill Pond, suggests the beginning of Hingham’s commercial harbor. In later years, Hingham harbor’s many wharves were key to the success transporting goods produced by local tradesmen to Boston and beyond.

suggested the steeple of Old Ship Church (not yet built) to help locate the site of an earlier meetinghouse on Main Street. At the harbor a single wharf, likely located at the mouth of Mill Pond, suggests the beginning of Hingham’s commercial harbor. In later years, Hingham harbor’s many wharves were key to the success transporting goods produced by local tradesmen to Boston and beyond. The viewer may be surprised at the prominence of Mill Pond—how it extends in the distance to what is now Home Meadows. This once broad expanse of water carried early settler Peter Hobart and company to their landing point at the foot of Ship Street at North Street. Mill Pond, flushed by tidal waters and fed by the Town Brook, is, alas, no longer. In the late 1940s it was “paved over for a parking lot” along Station Street and the historic brook sent underground. The vestige of Mill Pond’s shoreline still remains, along the rear of old buildings lining the south side of North Street.

The viewer may be surprised at the prominence of Mill Pond—how it extends in the distance to what is now Home Meadows. This once broad expanse of water carried early settler Peter Hobart and company to their landing point at the foot of Ship Street at North Street. Mill Pond, flushed by tidal waters and fed by the Town Brook, is, alas, no longer. In the late 1940s it was “paved over for a parking lot” along Station Street and the historic brook sent underground. The vestige of Mill Pond’s shoreline still remains, along the rear of old buildings lining the south side of North Street. Research was important to surmise how Hingham Harbor may have first appeared to arriving settlers. I found no local 17th century drawings or paintings on which to base the design. Instead I used a variety of sources to help me understand what might be a plausible view. My research included:

Research was important to surmise how Hingham Harbor may have first appeared to arriving settlers. I found no local 17th century drawings or paintings on which to base the design. Instead I used a variety of sources to help me understand what might be a plausible view. My research included: