In this final part of my blog about the Sprague family, I’ll highlight descendants of Ralph Sprague, the oldest of the three brothers who came to the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1628.

In the books written about Ralph Sprague and his family, Ralph is most highly regarded for his service to the Massachusetts Bay Colony.

In The Founding of Charlestown by the Spragues, A Glimpse of the Beginning of the Massachusetts Bay Settlement (1910), written by Henry H. Sprague, the author quotes the earlier historian Richard Frothingham, Jr., who wrote of Ralph Sprague in The History of Charlestown (1845):

He was a prominent and valuable citizen – active in promoting the colony.

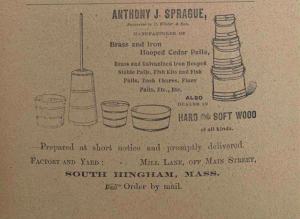

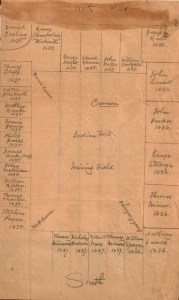

The Spragues of Malden, Massachusetts (Hingham Historical Society archives)

And in The Spragues of Malden, Massachusetts, by George Walter Chamberlain, this is written about Ralph’s contributions:

Ralph Sprague served as a Deputy to the General Court from Charlestown, then including Everett, Malden, Melrose, Stoneham and Somerville, etc., in at least sixteen sessions and served on important committees many times. The fact that Mr. Sprague served with the most distinguished men of the Massachusetts Bay Colony so long indicates that he was a man of sound judgment and remarkable ability. His influence in the Colony was great.

While Ralph first built a home for his family in Charlestown, he was later given more land:

In 1638 the Town of Charlestown made a record of twelve lots of land which were granted to him. Five of these lots were on Mystic Side, out of which the town of Malden was formed in 1649.

Within a decade, Ralph Sprague was helping to establish the Town of Malden.

On 1 Jan. 1648/9, Lt. Ralph Sprague and nine other freemen . . . petitioned the General Court of Massachusetts Bay Colony, for a separation from Charlestown, and Misticke side became a distinct town of the name Maulden, 11 May 1649.

This post is intended to focus on historically prominent descendants of Ralph Sprague of Charlestown and Malden who were 19th and 20th century scientists, inventors, and industrialists. But permit me a diversion first to highlight some of Ralph’s descendants who made their mark during their time, though they are less remembered now:

Dr. John C. Sprague (1754-1803) of Malden, a descendant of Ralph’s son John Sprague, did military service as a  surgeon, was twice captured by the British, and was imprisoned for a time in Ireland. After the War for Independence, he became a schoolteacher and also was involved in Malden Town government, serving on a wide range of Committees. At a special Town Meeting in 1797, Dr. Sprague was elected both to a committee on education and to a committee to raise money for the encouragement of singing. In noting this specific service, the author of The Spragues of Malden adds: “Thus was Dr. Sprague identified with the best things of his native town in the reconstructive period following the Revolutionary War.”

surgeon, was twice captured by the British, and was imprisoned for a time in Ireland. After the War for Independence, he became a schoolteacher and also was involved in Malden Town government, serving on a wide range of Committees. At a special Town Meeting in 1797, Dr. Sprague was elected both to a committee on education and to a committee to raise money for the encouragement of singing. In noting this specific service, the author of The Spragues of Malden adds: “Thus was Dr. Sprague identified with the best things of his native town in the reconstructive period following the Revolutionary War.”

Phineas Sprague (1777-1869) of Malden—the 5th in a line of men named Phineas descended from Ralph’s son John, was a delegate to the Constitutional Convention of Massachusetts in 1820, at which he spoke on the Declaration of Rights, saying: “It is tyranny in the highest degree to compel a man to worship in a manner contrary to the dictates of his conscience. Religion is an affair between God and our own souls.”

Phineas’ liberal views regarding religion, like those we in Hingham associate with the minister at First Parish, Ebenezer Gay (1696-1787) in the early days of what was first known as the Arminian movement, eventually led Phineas to withdraw from First Parish of Malden. Phineas later would be involved in establishing a Universalist church in Malden.

Dr. John’s son, John Sprague (1781-1852) of Malden, like his cousin Phineas, espoused liberal views of religion at a time when religious congregations in New England were dividing due to differing theological views during what would be known in Protestantism as the Great Awakening, and then due to differing political views: Federalism vs. States Rights. (In Hingham, these political divisions led to the founding of New North Church by a group of Federalist-leaning residents including Major General Benjamin Lincoln.)

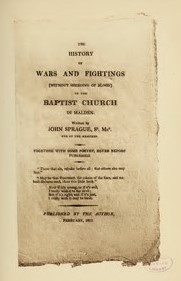

John was an original member of the First Baptist Church of Malden but later found himself unwelcome in the church due to his Arminian views vs. the Calvinist doctrines of the minister at the time. In 1812, John Sprague wrote and self-published a pamphlet that caused quite a stir: The History of Wars and Fightings (Without Shedding of Blood) in the Baptist Church in Malden. A subtitle reads “Together with Some Poetry, Never Before Published.”

On April 12, 1812, the members of the Baptist church based his exclusion from the congregation on the publication of this book. While John Sprague was a shoemaker by trade, he enjoyed writing poetry—and a few of his humorous poems are included in the The Spragues of Malden.

John was selected by the town of Malden for many committees, among them: the Bunker Hill Monument Association formed to raise money for the monument’s construction, and the committee formed by the town in 1844 to choose the best path through Malden for what was then called the Maine Railroad. I think many of those who serve on Town Committees in Hingham today would have enjoyed the company of shoemaker John Sprague of Malden.

Horatio Sprague Sr. (1784-1848), a descendant of Ralph’s son John, was born in Boston, but most associated with Gibraltar, where he permanently resided from 1815 until his death. Horatio was a merchant and ship owner in Gibraltar, a British territory on the tip of the Iberian Peninsula, when he was chosen to be U.S. Consul there in 1832. His duties, largely tied to facilitating commerce, were not onerous, but his health declined.

His son, Horatio Jones Sprague Jr. (1823-1901), who was born in Gibraltar and spoke several languages, was appointed after his father’s death as U.S. Consul in Gibraltar and served in that post for 53 years. His consular workload was greater than his father’s due to the opening of the Suez Canal in 1870, and two wars that had an impact during his tenure: the Civil War in the U.S. (1861-65) and the Spanish-American War (1898.) Horatio Sprague Jr. also broadened the business portfolio he’d developed with his father when he became an importer of tobacco to Gibraltar. Horatio died in 1901, and would be succeeded as U.S. Consul by his son, Richard Sprague (1871-1934.)

Details about this now-unusual Sprague diplomacy dynasty is on this website, serving fans of James Joyce. Why would such a James Joyce website include information about the Spragues of Gibraltar? I was surprised to learn that James Joyce’s famous work Ulysses (first serialized beginning in 1918, then published as a book in 1922) has a Horatio Sprague Jr. reference, as “old Sprague the consul”:

. . . when general Ulysses Grant whoever he was or did supposed to be some great fellow landed off the ship and old Sprague the consul that was there from before the flood dressed up poor man and he in mourning for the son.

While James Joyce’s Ulysses is a work of fiction, this reference to Ulysses Grant visiting Gibraltar is based on historic fact. The then former president, Ulysses Grant visited Gibraltar as part of a world tour in 1878, when the U.S. Consul there was Horatio Jones Sprague, Jr.

Now, on to those descendants of Ralph Sprague who made lasting contributions to science, innovation, and industry in the 19th and 20th centuries.

Charles H. Sprague (1827-1904) of Malden descended from Ralph’s son Phineas (1637-1690), who was among the Malden men who fought in King Philip’s War.

Charles served his local community as a member of the Malden City Council, following in the public service tradition of many Spragues over the centuries. And like other notable Spragues, Charles was a scientist as well as a prominent business leader.

Charles served his local community as a member of the Malden City Council, following in the public service tradition of many Spragues over the centuries. And like other notable Spragues, Charles was a scientist as well as a prominent business leader.

In 1849, Charles Sprague was appointed by the United States Government to the editorial staff of the American Ephemeris and Nautical Almanac, where he reported on astronomical observations. He held this position for fifteen years. American Ephemeris and Nautical Almanac was published, under the authority of the Secretary of the Navy, from 1855 to 1980, containing information necessary for astronomers, surveyors, and navigators. The Preface tothe 1855 edition reports “the preparation of this work was begun in the latter part of the year 1849, in accordance with an act of Congress, approved on the 3d of March of that year.” The publication continues now as The Nautical Almanac.

Charles went on, in 1870, to establish the Charles H. Sprague Company, a  privately-held power company focused on the market for coal during the early part of the industrial age. During World War I, the company became the major supplier of coal to America’s European allies. To facilitate the shipment of coal across the Atlantic, he also founded the Sprague Steamship Company which operated a large fleet of vessels serving many company-owned terminals.

privately-held power company focused on the market for coal during the early part of the industrial age. During World War I, the company became the major supplier of coal to America’s European allies. To facilitate the shipment of coal across the Atlantic, he also founded the Sprague Steamship Company which operated a large fleet of vessels serving many company-owned terminals.

Charles’ son and Malden native Phineas Warren Sprague (1860-1943) had been a partner of what had become C.H. Sprague & Son, and after his father’s death he assumed full control of the business. The company would later expand into oil and be renamed Sprague Energy. In 1942, the U.S. Government selected Sprague Energy to manage its wartime coal shipment program.

Sprague Energy, Quincy, Mass.

Charles’ grandson, Phineas Sprague Jr. (1901-1977) joined company management after World War II service in the Navy, from which he retired as a Lieutenant Commander. While the family sold its remaining interests in the company in 1970, the Sprague Energy brand is still in use, and has expanded into natural gas—including here on the South Shore, where the Sprague Energy brand is emblazoned at an oil terminal on Southern Artery along the Town River in Quincy, MA.

Frank Julian Sprague (1857-1934), another descendant from Ralph’s son John, was born in Milford, CT., was raised in North Adams, MA by an aunt and other relatives after his mother’s death when he was 9 years old. As a boy, Sprague became fascinated by the textile mills and related manufacturing operations in North Adams. He did quite well in school and went on to Annapolis where he studied electrical engineering. He worked briefly with Thomas Edison, but his major contributions came after he began working on his own inventions, for the electric motor, electric railways and electric elevators. His patented inventions made the electric streetcar a reliable means of transit for emerging “streetcar suburbs.” I enjoyed reading the biography: Frank Julian Sprague, by William D. Middleton, MD., published by Indiana University Press in 2009 (cover shown here), which chronicles his life as well as his many inventions.

North Adams, MA by an aunt and other relatives after his mother’s death when he was 9 years old. As a boy, Sprague became fascinated by the textile mills and related manufacturing operations in North Adams. He did quite well in school and went on to Annapolis where he studied electrical engineering. He worked briefly with Thomas Edison, but his major contributions came after he began working on his own inventions, for the electric motor, electric railways and electric elevators. His patented inventions made the electric streetcar a reliable means of transit for emerging “streetcar suburbs.” I enjoyed reading the biography: Frank Julian Sprague, by William D. Middleton, MD., published by Indiana University Press in 2009 (cover shown here), which chronicles his life as well as his many inventions.

Frank lived with his family in New York City for much of his life. As a graduate of the Naval Academy and former Naval Officer, Frank was buried at Arlington National Cemetery.

Robert (1900-1991) and Julian (1903-1960) Sprague, sons of Frank Julian Sprague, became the co-founders, in 1926, of one of the largest electric components companies of its time. The Sprague Specialties Company, founded by the brothers in Quincy, MA, moved to North Adams, MA in 1930. They chose North Adams due to their father’s fondness for his boyhood there. In 1942 the company changed its name to the Sprague Electric Company.

The company expanded in 1942—buying the factory buildings that previously housed the Arnold Print Works textile firm. The 16 acres of grounds on the Hoosic River in North Adams, Massachusetts, encompass a vast complex of 19th-century mill buildings and occupy nearly one-third of the city’s downtown business district. This was the home of Sprague Electric Company until 1985. At its peak, Sprague Electric was one of the largest electronic component manufacturers in the world.

John Louis Sprague, Sr. (1930-2021), Robert’s son, would be the last Sprague to head the Sprague Electric Company. John Sprague was a chemist who joined the company soon after completing his PhD at Stanford in the late 1950s. He would spend 11 years as president of Sprague Electric. John’s son, John Sprague Jr., wrote a blog, available at www.spraguelegacy.com about his dad’s role with the company. The website also chronicles the history of the Sprague Electric Company.

The Sprague Electric Company was sold in 1976. John Sprague was still president (under the new ownership) in 1984 and 1985 when company owner Penn Central moved the company’s international headquarters from the Berkshires to Lexington and eliminated 700 Sprague jobs in North Adams. That move, the Berkshire Eagle later reported, “left a legacy of bitterness in the city,” even though Sprague didn’t completely leave North Adams until the early 1990s.

Innovation and the Arts

(Photo courtesy of MassMoCA.org)

Given the history of this family in both the arts and sciences, it seems so appropriate that what was the Sprague factory complex in North Adams has become Mass MOCA—an art museum, known for its embrace of innovation across the visual arts and, in more recent history, performing arts as well.

After years of planning, fund-raising and some additional construction on the former factory site, MASS MoCA celebrated its opening in 1999, as the center’s website says: “marking the site’s launch into its third century of production, and the continuation of a long history of innovation and experimentation.”

That “long history of innovation and experimentation” certainly applies to the contributions over generations of the creative Sprague family as well. Perhaps both nature and nurture played a role. An impressive legacy.

SOURCES not otherwise referenced:

Portraits of John, Charles H., and Phineas W. Sprague from Historic Homes and Places and Genealogical and Personal Memoirs Relation to the Families of Middlesex County, Massachusetts, vol. III (Cutter, ed., 1908)

Obituaries of Charles H. Sprague published in the Boston Daily Globe, July 1, 1904; and the Springfield Republican (Massachusetts) June 30, 1904.

The History of Malden, Massachusetts 1633-1785

Malden Past and Present: 1649-1899, pub. May, 1899.

The website www.spragueenergy.com

Special thanks to my friend Paula Bagger who provided many of the images of items from the Hingham Historical Society archives–for part 2 of this blog in particular.

################

which is show here. The Hingham Library also has an original edition in its Sprague family archive. This genealogy is notable as it was published well-before the popularity of genealogies in the late 19th/early 20th century, following the 1876 U.S. centennial and the 1890 launch of the Daughters of the American Revolution, when charting colonial ancestry became quite popular.

which is show here. The Hingham Library also has an original edition in its Sprague family archive. This genealogy is notable as it was published well-before the popularity of genealogies in the late 19th/early 20th century, following the 1876 U.S. centennial and the 1890 launch of the Daughters of the American Revolution, when charting colonial ancestry became quite popular.

In 2014-15,

In 2014-15,

Brothers Ralph (1599-1650), Richard (1605-1668) and William Sprague (1609-1675), were sons of Edward Sprague (1576-1614), who operated a fulling mill on the river Wey, in Upwey, located between Dorchester and Weymouth, in the county of Dorset, England. (Edward’s mill, shown here, no longer exists.) After their father’s death, the three brothers joined a party of colonists emigrating for the Mass Bay Company to settle what became Charlestown, Massachusetts. It is unclear if religion was part of the Sprague brothers’ motivation to leave England. They arrived in Salem in 1628, then soon traveled on to Charlestown.

Brothers Ralph (1599-1650), Richard (1605-1668) and William Sprague (1609-1675), were sons of Edward Sprague (1576-1614), who operated a fulling mill on the river Wey, in Upwey, located between Dorchester and Weymouth, in the county of Dorset, England. (Edward’s mill, shown here, no longer exists.) After their father’s death, the three brothers joined a party of colonists emigrating for the Mass Bay Company to settle what became Charlestown, Massachusetts. It is unclear if religion was part of the Sprague brothers’ motivation to leave England. They arrived in Salem in 1628, then soon traveled on to Charlestown.

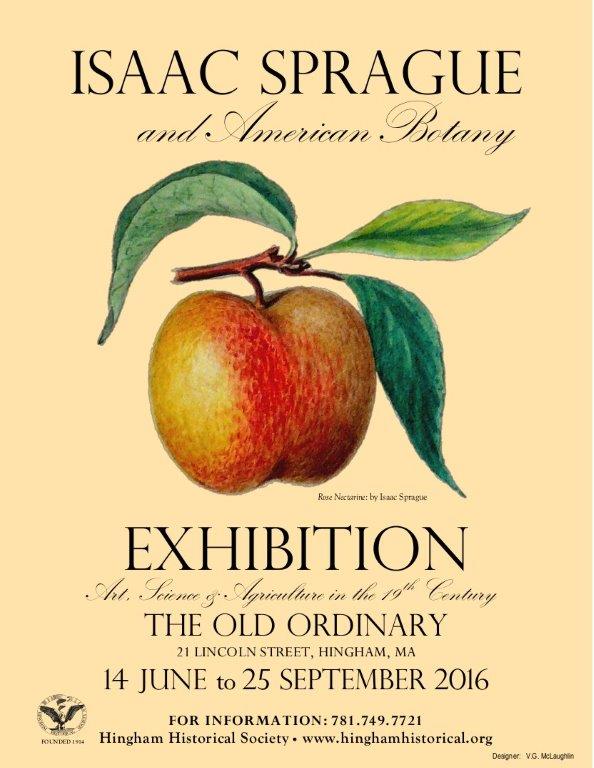

A new exhibit opened today at our 1688

A new exhibit opened today at our 1688

After his trip west Sprague returned briefly to the South Shore, working as a clerk in a Nantasket Beach hotel until, the following year, he started to work as an illustrator for prominent American botanist

After his trip west Sprague returned briefly to the South Shore, working as a clerk in a Nantasket Beach hotel until, the following year, he started to work as an illustrator for prominent American botanist