Dr. Robert Thaxter was born in Hingham on October 21, 1776, only months after the 13 American colonies declared their independence from Great Britain. This was of course a year symbolic of strength, resilience and change, and the same can be said of Dr. Thaxter, who possessed this type of fortitude and a commitment to helping others that one day would claim his life.

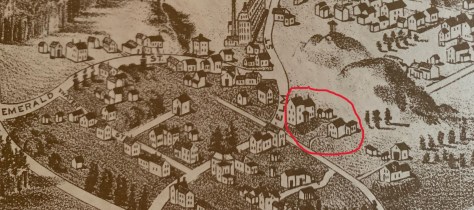

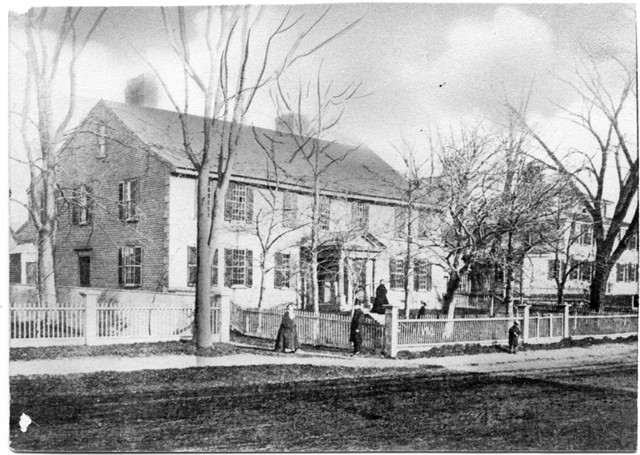

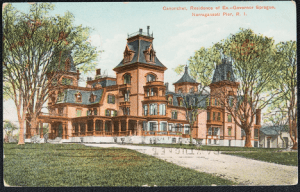

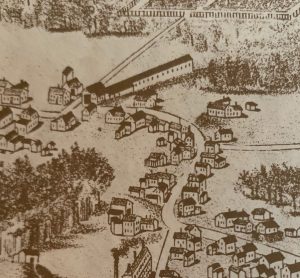

Tranquility Lodge, 137 Main Street, Hingham

Likely born in his grandparents’ house at 21 Lincoln Street (now known as the Hingham Historical Society’s Old Ordinary), Robert Thaxter grew up at 137 Main Street in Hingham, a lovely home once called “Tranquility Lodge,” sitting just down aways on Main Street from Hingham’s 1681 Old Ship Church Meeting House.

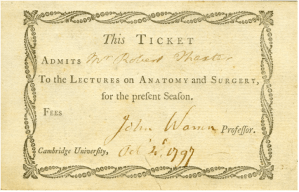

He graduated from Harvard College in 1798 and attended the highly selective private cadaver lectures in Anatomy and Surgery offered by the famous surgeon Dr. John Warren (1753-1815), who would go on to be a founder of Harvard Medical School. Dr. Robert Thaxter’s original admission ticket to Dr. Warren’s class is seen below. Robert soon joined the Massachusetts Medical Society and in 1824 delivered that body’s annual oration, titled A Dissertation on the Excessive Use of Ardent Spirits.

Robert continued a family tradition as a highly respected medical doctor. He was mentored by and practiced with his father, Dr. Thomas Thaxter, in the study of medicine and surgery in Hingham. Dr. Thomas Thaxter was of deep Hingham roots, as “the family of Thaxters were among the early settlers of that town.” (The Boston Medical and Surgical Journal, Vol, XLVI., Wednesday, May 19, 1852. No.16 pg. 309)

Robert continued a family tradition as a highly respected medical doctor. He was mentored by and practiced with his father, Dr. Thomas Thaxter, in the study of medicine and surgery in Hingham. Dr. Thomas Thaxter was of deep Hingham roots, as “the family of Thaxters were among the early settlers of that town.” (The Boston Medical and Surgical Journal, Vol, XLVI., Wednesday, May 19, 1852. No.16 pg. 309)

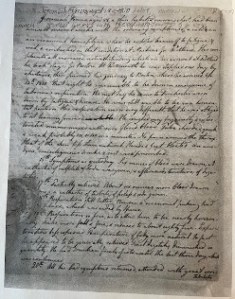

Dr. Robert Thaxter kept detailed records of his patients. His medical diary is a treasure that the Hingham Historical Society holds in its archives. He had a unique writing style and in one journal entry describes the travels of a critically ill man who journeyed from northern Maine for medical care.

This was a demanding trip in the 19th century even for a healthy person let alone one with a critical illness. But Dr. Thaxter was a physician of both the rich and the poor and a healer with an extensive reputation as a doctor both near and far. The doctor’s notes reflect his high level of compassion for this distressed patient. His concise description of the patient’s clinical findings also shows a modernist sensibility in terms of his ability to describe clinical findings with a degree of precision. At that time, treating patients was limited by the lack of today’s medicines such as antibiotics which may have cured this patient. Dr. Thaxter did a remarkable job taking care of patients with the limited pharmacopoeia available at that time. Dr. Thaxter’s 1810 entry regarding his examination of this sick patient is as follows.

This was a demanding trip in the 19th century even for a healthy person let alone one with a critical illness. But Dr. Thaxter was a physician of both the rich and the poor and a healer with an extensive reputation as a doctor both near and far. The doctor’s notes reflect his high level of compassion for this distressed patient. His concise description of the patient’s clinical findings also shows a modernist sensibility in terms of his ability to describe clinical findings with a degree of precision. At that time, treating patients was limited by the lack of today’s medicines such as antibiotics which may have cured this patient. Dr. Thaxter did a remarkable job taking care of patients with the limited pharmacopoeia available at that time. Dr. Thaxter’s 1810 entry regarding his examination of this sick patient is as follows.

Jeremiah Ferino: Jeremiah, 28, a thin habit, (and) narrow chest, had been unwell several weeks with the ordinary symptoms of a cold an occasional haemophysis, when he exhaled himself to fatigue (and) … (and) embarked in that condition at Machias for Portland.

His complaints all increased notwithstanding which on his arrival at Portland he took stage for Boston. At Portsmouth he was stopped one day by epistaxis then … his journey to Boston, where he arrived April 14th, 1810.

That night he was unable to lie down in consequence of laborious respiration. The next day he came to Dorchester worn down by fatigue (and) disease. He was still unable to lie in a horizontal position. His respiration was so very difficult that he was obliged to sit leaning forward. He coughed very frequently (and) expectorated mucous mixed with very (fluid) blood.

To have medicines on hand as a doctor, his father, Dr. Thomas Thaxter was also proprietor of a pharmacy in Hingham, which Robert’s maiden aunt, Abigail Thaxter, ran. (History of the Town of Hingham, 1893; Vol II, page 323; “Native and Resident Physicians” by George Lincoln.) The Thaxter pharmacy would have had a wealth of compounds, elixirs, herbs, and other medicinal items that the young Robert Thaxter could access to treat and cure ailments of that time. Dr. Robert Thaxter’s beautiful wooden medicine chest is also in the collection of the Hingham Historical Society. His medicine chest contains thirteen mold blown glass bottles, many of them with original paper labels. The bottles are labeled with interesting ingredients such as maraschino, strawberry syrup, ginger, parfait amour, rose water, spirit of camphor, orange, oil of cinnamon, oil of cloves, and aromatic elixir. Today, most of these items would be found in our kitchen spice rack rather than our medicine cabinet.

Once trained, Robert Thaxter stayed in Hingham side by side with his father and continued the medical practice. They were both driven and ambitious men but by 1809, Dr. Robert Thaxter needed his independence. He moved his medical practice to Dorchester. Not surprisingly, he was “immediately received into popular confidence which he retained until his death.” (The Boston Medical and Surgical Journal, Vol, XLVI., Wednesday, May 19, 1852. No.16 pg.309). Dr. Thaxter was married to his love of medicine and never took a wife. Once settled in Dorchester, he posted the following advertisement in the July 22, 1809 Columbian Centinel Newspaper:

NOTICE: Doctor Robert Thaxter informs the Inhabitants of Dorchester that he has taken lodgings at the residence of Mr. William Richards, where he will be ready at all times to attend to his profession. He will inoculate with kine Pox, free of expense, all persons who feel themselves unable to pay.

(History of the Town of Hingham, 1893; Vol II, page 324. “Native and Resident Physicians” by George Lincoln.)

At that time, Boston was a homogeneous and in many ways provincial society, with a deeply rooted regard for its protestant English past. Irish immigrants now flooded into Boston hoping for a second chance in life. These Catholic newcomers, though, were seen as a threat to the norms of Boston society. Dr. Thaxter’s decision to relocate his practice to Dorchester was a bold move. He might have damaged his reputation as a doctor by leaving, but he didn’t and still returned to the area to perform surgeries (The Boston Medical and Surgical Journal, Vol, XLVI., Wednesday, May 19, 1852. No.16 pg.309).

Once settled in Dorchester his reputation took off. Dr. Thaxter’s diligence, careful medical observation, and never-ending dedication to the sick expanded his medical practice to neighboring areas. As time went on, he also was drawn to the Irish poor now arriving in Dorchester. “The Irish population gathered more thickly about him . . . . By night and by day, he was at their beck,” (The Boston Medical and Surgical Journal, Vol, XLVI., Wednesday, May 19, 1852. No.16 pg.312)

Dr. Thaxter’s commitment as a doctor to serving the needy, poor, and especially, those from Ireland fleeing the potato famine is commendable—then and now. Those emigrating by what were later called “coffin ships” from Ireland carried poor passengers in steerage where there was a lack of food, plenty of filth and diseases running rampant such as typhus. (As described in a Hingham Historical Society lecture, “The Irish Riviera and Hingham’s Irish 1850-1950,” available for viewing here, typhus and other infectious diseases were killers without our present-day antibiotics.

Dr. Thaxter met his end doing what he believed in. “He fell a martyr to the ship fever (typhus fever), caught in attending an Irish family, just from on board ship.” (Obituary, Boston Daily Evening Transcript 11 Feb 1852). It was said that “Dr. Thaxter never stopped helping the Irish.” (Ibid.) He had a charitably rich and spiritual life to the end. Dr. Thaxter died February 9th, 1852. He was 75 years old. (History of the Town of Hingham, 1893; Vol II, page 324; “Native and Resident Physicians” by George Lincoln.)

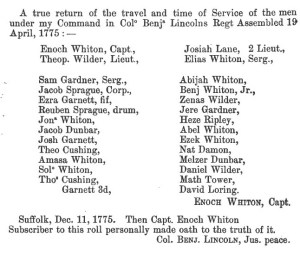

To learn more about the Thaxter family and its place in local and American history, please see our post One if By Land, Two If By Sea on this blog. You might also look at the recent publication, Revolutionary War Patriots of Hingham, by Ellen Miller and Susan Wetzel, Dec 26, 2023, which details the town’s Patriots, including quite a few from the Thaxter family who left their mark in history.

Abigail (Smith) Thaxter

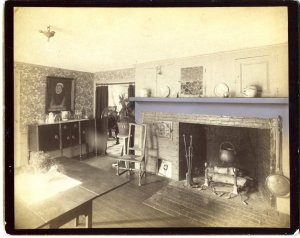

If you are in Hingham, you also may want to visit Dr. Thaxter’s likely birthplace, the Old Ordinary. There you can see a portrait of Dr. Robert Thaxter’s grandmother, Abigail Smith Thaxter, hanging in the parlor.

Dr. Robert Thaxter’s spirit carries on today in public service and health. This tradition of outreach and assistance to those most disadvantaged continues in the Boston area such as the work of the late Dr. Paul Farmer and the continuing work of Partners in Health, and Dr. Jim O’Connell and Boston Health Care for the Homeless, as well as numerous others dedicating their lives to helping those in need.

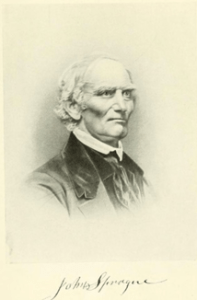

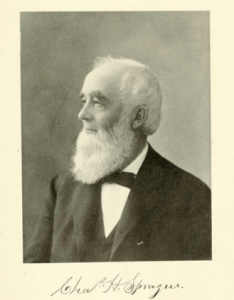

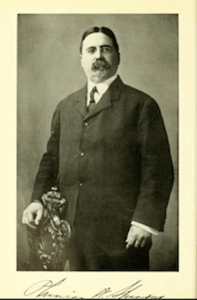

Charles served his local community as a member of the Malden City Council, following in the public service tradition of many Spragues over the centuries. And like other notable Spragues, Charles was a scientist as well as a prominent business leader.

Charles served his local community as a member of the Malden City Council, following in the public service tradition of many Spragues over the centuries. And like other notable Spragues, Charles was a scientist as well as a prominent business leader. privately-held power company focused on the market for coal during the early part of the industrial age. During World War I, the company became the major supplier of coal to America’s European allies. To facilitate the shipment of coal across the Atlantic, he also founded the Sprague Steamship Company which operated a large fleet of vessels serving many company-owned terminals.

privately-held power company focused on the market for coal during the early part of the industrial age. During World War I, the company became the major supplier of coal to America’s European allies. To facilitate the shipment of coal across the Atlantic, he also founded the Sprague Steamship Company which operated a large fleet of vessels serving many company-owned terminals.

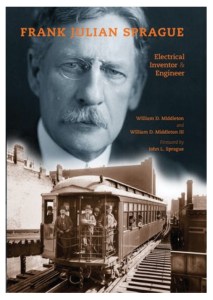

North Adams, MA by an aunt and other relatives after his mother’s death when he was 9 years old. As a boy, Sprague became fascinated by the textile mills and related manufacturing operations in North Adams. He did quite well in school and went on to Annapolis where he studied electrical engineering. He worked briefly with Thomas Edison, but his major contributions came after he began working on his own inventions, for the electric motor, electric railways and electric elevators. His patented inventions made the electric streetcar a reliable means of transit for emerging “streetcar suburbs.” I enjoyed reading the biography: Frank Julian Sprague, by William D. Middleton, MD., published by Indiana University Press in 2009 (cover shown here), which chronicles his life as well as his many inventions.

North Adams, MA by an aunt and other relatives after his mother’s death when he was 9 years old. As a boy, Sprague became fascinated by the textile mills and related manufacturing operations in North Adams. He did quite well in school and went on to Annapolis where he studied electrical engineering. He worked briefly with Thomas Edison, but his major contributions came after he began working on his own inventions, for the electric motor, electric railways and electric elevators. His patented inventions made the electric streetcar a reliable means of transit for emerging “streetcar suburbs.” I enjoyed reading the biography: Frank Julian Sprague, by William D. Middleton, MD., published by Indiana University Press in 2009 (cover shown here), which chronicles his life as well as his many inventions.

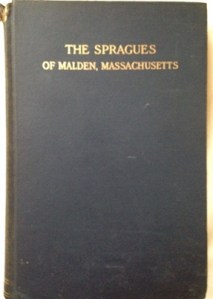

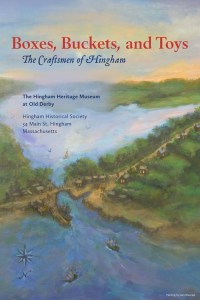

which is show here. The Hingham Library also has an original edition in its Sprague family archive. This genealogy is notable as it was published well-before the popularity of genealogies in the late 19th/early 20th century, following the 1876 U.S. centennial and the 1890 launch of the Daughters of the American Revolution, when charting colonial ancestry became quite popular.

which is show here. The Hingham Library also has an original edition in its Sprague family archive. This genealogy is notable as it was published well-before the popularity of genealogies in the late 19th/early 20th century, following the 1876 U.S. centennial and the 1890 launch of the Daughters of the American Revolution, when charting colonial ancestry became quite popular.

In 2014-15,

In 2014-15,

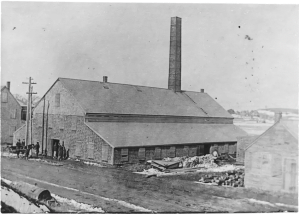

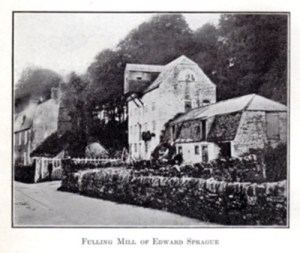

Brothers Ralph (1599-1650), Richard (1605-1668) and William Sprague (1609-1675), were sons of Edward Sprague (1576-1614), who operated a fulling mill on the river Wey, in Upwey, located between Dorchester and Weymouth, in the county of Dorset, England. (Edward’s mill, shown here, no longer exists.) After their father’s death, the three brothers joined a party of colonists emigrating for the Mass Bay Company to settle what became Charlestown, Massachusetts. It is unclear if religion was part of the Sprague brothers’ motivation to leave England. They arrived in Salem in 1628, then soon traveled on to Charlestown.

Brothers Ralph (1599-1650), Richard (1605-1668) and William Sprague (1609-1675), were sons of Edward Sprague (1576-1614), who operated a fulling mill on the river Wey, in Upwey, located between Dorchester and Weymouth, in the county of Dorset, England. (Edward’s mill, shown here, no longer exists.) After their father’s death, the three brothers joined a party of colonists emigrating for the Mass Bay Company to settle what became Charlestown, Massachusetts. It is unclear if religion was part of the Sprague brothers’ motivation to leave England. They arrived in Salem in 1628, then soon traveled on to Charlestown.

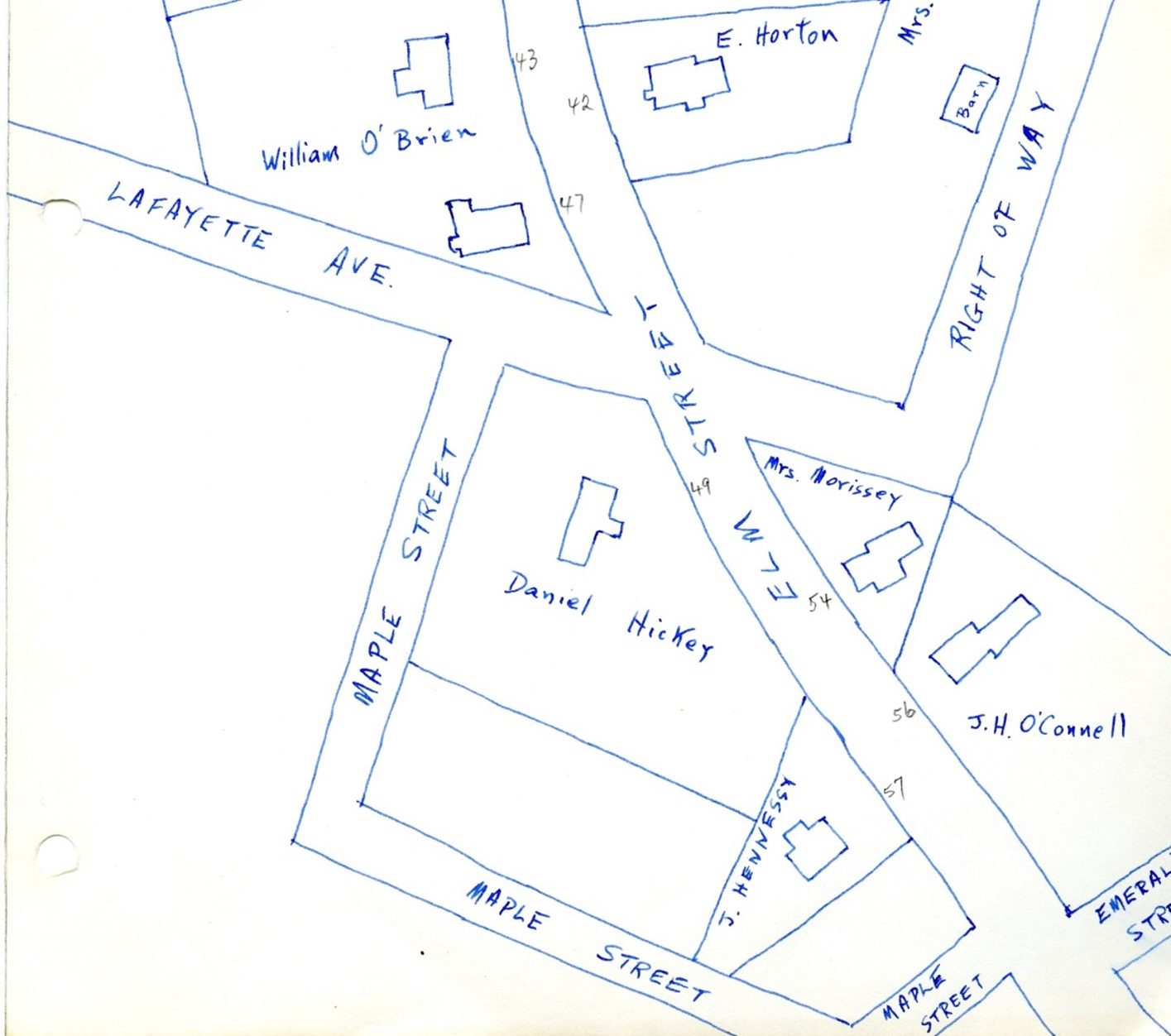

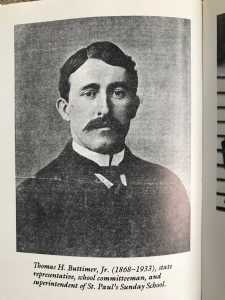

Jr., who in 1900 had his own family home on Lincoln Street, was a prominent attorney, and in 1902 would be elected as state representative from the 3rd district. Over on Green Street, Aunt Judith must have been quite proud, although in 1902, as a woman, she would not yet have had the right to vote.

Jr., who in 1900 had his own family home on Lincoln Street, was a prominent attorney, and in 1902 would be elected as state representative from the 3rd district. Over on Green Street, Aunt Judith must have been quite proud, although in 1902, as a woman, she would not yet have had the right to vote.

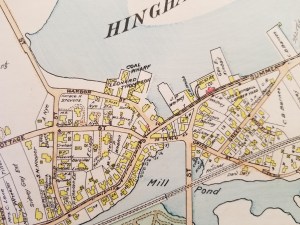

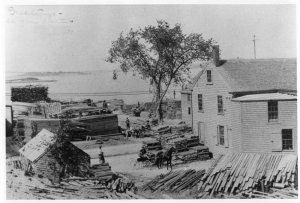

But Green Street’s location near the harbor gave its residents convenient access to work related to the coal and wood fuel-supply dealers, lumber wharves, and other harbor-related businesses. For many, this proximity to businesses needing carting and other hauling and loading services created jobs as teamsters, or as hostlers. Teamsters living on Green Street in 1900 included the recently married Cornelius Ryan, 31, and William Welch, 33 and married with young children.

But Green Street’s location near the harbor gave its residents convenient access to work related to the coal and wood fuel-supply dealers, lumber wharves, and other harbor-related businesses. For many, this proximity to businesses needing carting and other hauling and loading services created jobs as teamsters, or as hostlers. Teamsters living on Green Street in 1900 included the recently married Cornelius Ryan, 31, and William Welch, 33 and married with young children.

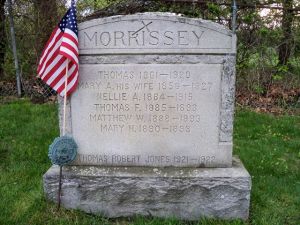

the Morrsisseys, 1900 was just seven years since the tragic loss of three of their young children to scarlet fever. The children’s young lives are memorialized on the family headstone at St. Paul’s Cemetery. Both Thomas and Mary were born in Irish immigrant households in Hingham. Thomas grew up on Elm Street. Mary’s parents earlier had a home on Green Street but after her dad’s death, her mother Ellen Crehan lived with her youngest daughter Catherine’s family here.

the Morrsisseys, 1900 was just seven years since the tragic loss of three of their young children to scarlet fever. The children’s young lives are memorialized on the family headstone at St. Paul’s Cemetery. Both Thomas and Mary were born in Irish immigrant households in Hingham. Thomas grew up on Elm Street. Mary’s parents earlier had a home on Green Street but after her dad’s death, her mother Ellen Crehan lived with her youngest daughter Catherine’s family here.

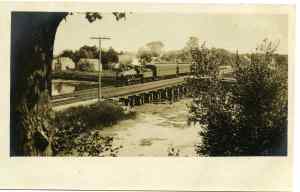

boarder, Michael Wallace, also a railroad worker. Taking in boarders was a common practice in the Irish community here, both to assist newer immigrants and to provide added income for the household. The children in the Kelly household as of 1900 included four daughters and two sons, all under ten years old. Another daughter would be born in 1901. Three of the “Kelly girls” of Green Street would, years later, be among the first women in Hingham to

boarder, Michael Wallace, also a railroad worker. Taking in boarders was a common practice in the Irish community here, both to assist newer immigrants and to provide added income for the household. The children in the Kelly household as of 1900 included four daughters and two sons, all under ten years old. Another daughter would be born in 1901. Three of the “Kelly girls” of Green Street would, years later, be among the first women in Hingham to

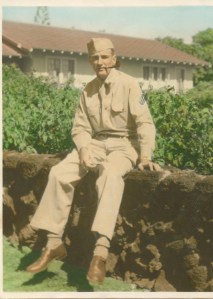

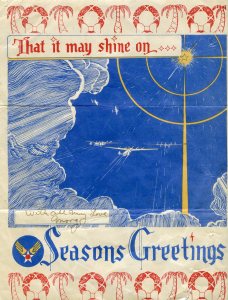

Hingham native Oliver L. (“Morg”) Ferris (1918-1985) served in the Army Air Corps as an airplane mechanic stationed in Hawaii and Guam, achieving the rank of Sergeant. He was a married man when he entered the service; while he was abroad, his wife, Margaret (“Rita”) Ferris, lived with her parents, the Scanlans, in Dorchester. For Christmas 1944, Morg sent Rita and her parents an Army Air Corps Christmas card which he signed on the front: “With all my love, Morg.” The card, postmarked December 9, 1944, shows aircraft in formation flying out of clouds towards what looks like a Christmas star. Between border decorations of palm trees and holiday wreaths at the top and bottom, it includes an inspirational, mission-driven message: “That It Might Shine On.”

Hingham native Oliver L. (“Morg”) Ferris (1918-1985) served in the Army Air Corps as an airplane mechanic stationed in Hawaii and Guam, achieving the rank of Sergeant. He was a married man when he entered the service; while he was abroad, his wife, Margaret (“Rita”) Ferris, lived with her parents, the Scanlans, in Dorchester. For Christmas 1944, Morg sent Rita and her parents an Army Air Corps Christmas card which he signed on the front: “With all my love, Morg.” The card, postmarked December 9, 1944, shows aircraft in formation flying out of clouds towards what looks like a Christmas star. Between border decorations of palm trees and holiday wreaths at the top and bottom, it includes an inspirational, mission-driven message: “That It Might Shine On.” Air Corps, but his choice of Christmas card could not have been more different! Richard served in the National Guard from 1939 to 1940 and, from 1941 to 1945, with the Army Air Corps as a member of the 3rd Bomber Group, which took the nickname “The Grim Reapers.”

Air Corps, but his choice of Christmas card could not have been more different! Richard served in the National Guard from 1939 to 1940 and, from 1941 to 1945, with the Army Air Corps as a member of the 3rd Bomber Group, which took the nickname “The Grim Reapers.” While the card is undated and bears no postmark, the context suggests it may have been sent for Christmas 1943, when the Third Bomber Group was indeed very “busy” with aerial bombing of New Guinea, as the allies fought a lengthy campaign to win New Guinea, which had been invaded by the Japanese in 1942. (Shown here: the 3rd Bomber Group attacks Japanese ships in Simpson Harbor, New Guinea, Nov. 2, 1943. Photo courtesy of the

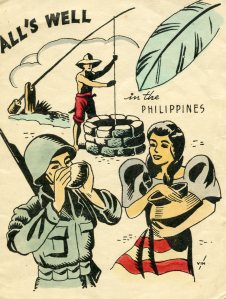

While the card is undated and bears no postmark, the context suggests it may have been sent for Christmas 1943, when the Third Bomber Group was indeed very “busy” with aerial bombing of New Guinea, as the allies fought a lengthy campaign to win New Guinea, which had been invaded by the Japanese in 1942. (Shown here: the 3rd Bomber Group attacks Japanese ships in Simpson Harbor, New Guinea, Nov. 2, 1943. Photo courtesy of the  undated card, sent to Morg and Rita, riffs on exotic travel posters of the day, featuring a four-color picture of a G.I. drinking from a coconut shell or wooden bowl offered by a native woman, while a native man operates a well nearby. “All’s Well in the Philippines,” the card reassures the recipient (albeit with a very bad pun). Inside, Ed has carefully handwritten the names of various cities in the Philippines in a style suggestive of steamer trunk labels and wrote:

undated card, sent to Morg and Rita, riffs on exotic travel posters of the day, featuring a four-color picture of a G.I. drinking from a coconut shell or wooden bowl offered by a native woman, while a native man operates a well nearby. “All’s Well in the Philippines,” the card reassures the recipient (albeit with a very bad pun). Inside, Ed has carefully handwritten the names of various cities in the Philippines in a style suggestive of steamer trunk labels and wrote: