From the 1880s through about 1920, Irish immigration to America was led by women. Fleeing poverty and lack of opportunity in their native land, they came alone or with a friend or cousin. They took jobs as domestic servants or mill workers, managing to send a bit of money home, which enabled other family members to follow. In Hingham, we see this unique immigration pattern played out in the life of Hannah Ferris. Whether or not she paid her brothers’ passage, she and her husband, Henry Trowbridge took them in when they came.

Hannah Ferris Trowbridge (1856-1934)

Hannah (Ferris) Trowbridge and Henry Trowbridge, circa 1885

She came, Hannah Ferris, a young woman, out of the impoverished west of Ireland early in the 1880s. She came, first, to the industrial town in central Massachusetts where she found work as a servant. In the summer of 1884, she came to Hingham, the bride of Henry Trowbridge, farmer, butcher, shop owner, and Civil War vet. He was more than a dozen years her senior, a recent widower, with no children.

How Henry and Hannah met is unknown. There were a number of Irish families in town. Henry’s cousin had a live-in Irish servant as did his several of his neighbors. Did one of them introduce the couple? Someone had to because she lived in Worcester, he lived in Hingham, and because more than miles separated them. She was a domestic servant; he was a business owner. She was Catholic; he held a pew in the Old Ship.

Raymond Trowbridge (1896-1962), son of Henry and Hannah, as a child. Raymond was a WWI and WWII Navy vet. His father was a Civil War Naval Vet.

They married in the Catholic church in Worcester in July 1884 and returned to Hingham where she moved into his house on the corner of Union and Pleasant streets. They had five children. Three of them died young. Their first born, Isabel, died of croup at “2 years, 2 months, 2 days.” Frances died of meningitis at 15 months, and they lost Henry Jr. to tuberculosis at 14. The Catholic cemetery was still new when they buried their young ones.

Henry was more than busy with work, farming, and family, but in 1982, he undertook a new project. He built three new houses on his Pleasant/Union Street property: a new one for his family and two others that came in handy when his relatives needed them and when Hannah’s brothers started coming to town.

* * * *

Hannah Ferris was the second of twelve children born in a small cottage in rural Killarney. Eight of her siblings immigrated into Massachusetts. Her younger sister Kate went to Worcester where she married, died and was buried in an unmarked grave with her six-month old son. Her seven brothers started their new lives in Boston or Worcester and have stories of their own, several marred by tragedy. The brothers were all in Hingham at some time, and many of their names are inked into St. Paul’s Church records as Godfather to one of Hannah’s children. Of the seven brothers, Morgan, Robert and Daniel lived in Hingham.

Morgan Ferris, my great-grandfather (1859-1938)

The Morgan Ferris family, School Street, 1921. Front, from left: Morgan Ferris, Oliver Tower, Oliver Ferris, Annie Tower, Annie (Tower) Ferris. Back, from left: Kathryn Ferris, Marjorie Ferris, Oliver Ferris, Amy (Litchfield) Ferris, Richard Ferris, Gordon Ferris.

Morgan Ferris came to Boston in about 1884 when he was in his twenties and soon followed Hannah to Hingham. He was a skilled carpenter and set up a business. Over the years, he built many houses on the South Shore. In 1892, he married Annie Tower, daughter of Oliver and Anne Tower of School Street. A minister of the First Baptist Church performed the ceremony in her family home; the record shows she was 19 and he was 29. (He was actually 33.) They bought a house on School Street at the intersection of Spring Street and had three children, Oliver, Kathyrn, and Gordon. All three children attended Hingham schools, married, and stayed in town. Oliver married Amy Litchfield, Katheryn, Bob McKenzie, and Gordon, Evelyn Staples. They, in turn, had children; many of them made Hingham their home.

Morgan died in 1938 at age 78. There are a few stories that came down the years; most are about his story-telling prowess and his big belly laugh. One is about his love of sports, another says that when he died, the rosary beads he brought with him from Ireland were found in his bureau drawer.

Robert Ferris (1868-1957)

In November 1892, twenty-three-year-old Robert Ferris married Irish-born Margaret McCarthy, a laundress, in Boston. At the time, he was living in Hingham with Henry and Hannah and, more than likely, working on building their new houses. He was a carpenter like several of the brothers, but he wanted something else and became a Boston police officer. He and his family moved closer to the city, and he returned the Union Street house to Hannah in a legal transaction. He began his career patrolling the South Boston waterfront. The only picture I have of him accompanies an article in The Boston Globe in 1901 which recognizes him for saving a nine-year old boy from drowning. He and Margaret had three children and lived relatively long lives.

Daniel Ferris (b. 1874)

Daniel and Gertrude Ferris’ children, Frances and John, c. 1902.

In 1898, Daniel was a U.S. Marine stationed in Boston, but his home was with Henry and Hannah. In 1899, he married their next-door neighbor, Gertrude Stephenson, daughter of Ezra and Clara of Pleasant Street. Daniel was 23 and she was 20. According to the Hingham Journal, the marriage “took place at St. Paul’s parsonage” on a Wednesday night. After their marriage, the couple lived with her family. Their daughter Francis was born in 1900 and son John in 1901. Things did not go well, however. Daniel was arrested for theft, court martialed and discharged from the service. Soon after, he left Hingham. Gertrude took a job as shoemaker and lived with her parents before eventually moving to Bank Street.

Daniel disappeared from the record until September 12, 1918, when he completed a WWI draft registration card. On that day, he was a logger living in a camp in Washington state. In addition to the birthdate, we know he is “our” Daniel Ferris, because he reported his nearest relative to be Robert Ferris, Police Headquarters, Boston, Mass.

Daniel’s problems and subsequent move may have hit Hannah hard – he was her youngest. brother When she was 18, she had walked to a civil registration office in Ireland to report his birth: “Informant, Hannah Ferris, present at birth.”

* * * *

Hannah’s life was full and her door, it seems, was always open. She kept in touch with her brothers and their children. She was Godmother to many and responded when they needed help. When her brother Eugene’s wife died of a fall at their home in Malden, her body was brought to Hingham and buried in Hannah and Henry’s plot in St. Paul’s cemetery.

Henry died in 1930 at 87, “one of the oldest GAR men in the state.” When Hannah died four years later at 78, she left a detailed will. To her son Raymond she left $1,000, to her daughter Mabel went her house worth $4,100, and to St. Vincent DePaul, a Catholic charity committed to serving the poor and suffering, her entire savings of $3,269.93.

Hannah, Henry and four of their five children are buried in St. Paul’s Cemetery. Morgan and his family are buried in the Hingham Centre Cemetery.

The Trowbridge Ferris graves. Four of Henry and Hannah’s five children and Hannah’s sister-in-law, Emma, are buried here. Henry and Hannah’s names are on the other side.

Notes

- There are a number of good sources on the subject of Irish female immigration. “The Irish Bridget: Irish Immigrant Women in Domestic Service in America, 1840-1930 written by Margaret Lynch-Brennan, is a good one. N.Y.: Syracuse University Press, 2009.

- The National Women’s History Museum website says: “Strong female networks sustained the immigration flow of Irish women, even during times of economic depression … Irish women were the only immigrant group to establish immigration chains … Whereas other ethnic groups sent their sons to America, Ireland sent its daughters.” Raising a glass to Irish women, March14, 2017,

- On dates, names and ages: Hannah and Morgan consistently shaved four or five years off their ages on official documents. Their other siblings were only marginally more accurate. Daniel alternately used Donald as his first name.

- On quotations in this post: “2 years, 2 months, 2 days”: Isabel Trowbridge death notice, Hingham Journal, Nov. 13, 1887; “took place at St. Paul’s parsonage”: Hingham Journal, June 1899; “one of the oldest GAR men in the state”: Henry Trowbridge obituary, Daily Boston Globe, May 7, 1930.

- Eugene’s wife, Emma Ferris, 64, died in a fall from the second-story piazza of her Malden home. “She was cleaning rugs when the railing broke.” The Boston Globe, Sept. 1, 1923.

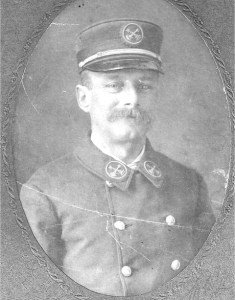

Martha and Rozy’s popularity was rooted in their love of community and volunteer work. Rozy had a successful meat market on Main Street in Hingham Centre. He was also an officer in Centre fire department, which he joined at age 18, fighting fires, keeping the records, and representing the department in parades and at conferences. Martha was “at home” as many women were—housekeeping being all consuming in the late nineteenth century. She was active in many organizations and raised money for a number of charities. She sang soprano in the First Parish choir and was an active members of the Women’s Relief Corps.

Martha and Rozy’s popularity was rooted in their love of community and volunteer work. Rozy had a successful meat market on Main Street in Hingham Centre. He was also an officer in Centre fire department, which he joined at age 18, fighting fires, keeping the records, and representing the department in parades and at conferences. Martha was “at home” as many women were—housekeeping being all consuming in the late nineteenth century. She was active in many organizations and raised money for a number of charities. She sang soprano in the First Parish choir and was an active members of the Women’s Relief Corps.

The triplets were given family names and not only did they all survive at a time when infant and child mortality was high, they all lived long lives. Hubbard and Polly lived to 78 and Lincoln to 80. This was so unusual that when, in 1889, the Burlington Weekly Free Press ran an article titled “Long-lived Triplets,” which featured three sets of New England triplets, the Litchfields were included.

The triplets were given family names and not only did they all survive at a time when infant and child mortality was high, they all lived long lives. Hubbard and Polly lived to 78 and Lincoln to 80. This was so unusual that when, in 1889, the Burlington Weekly Free Press ran an article titled “Long-lived Triplets,” which featured three sets of New England triplets, the Litchfields were included.

After several months of training in the north, the three young men left for the sounds of North Carolina aboard the USS Hetzel, a side-wheel steamer, chartered to maintain blockades on southern ports. In North Carolina, they transferred to the gunboat USS Louisiana, “five guns,”2 whose mission was to intercept blockade runners and support ground troops. The ship was crowded and damp, the weather humid and, in addition to the enemy, sailors fought the plethora of diseases that haunted ships. At some time that winter, George Merritt got sick. Suffering from intense fevers and chills, he was moved to a hospital in North Carolina. On February 7, 1863, he died of “swamp fever” and was buried “from the hospital.”2

After several months of training in the north, the three young men left for the sounds of North Carolina aboard the USS Hetzel, a side-wheel steamer, chartered to maintain blockades on southern ports. In North Carolina, they transferred to the gunboat USS Louisiana, “five guns,”2 whose mission was to intercept blockade runners and support ground troops. The ship was crowded and damp, the weather humid and, in addition to the enemy, sailors fought the plethora of diseases that haunted ships. At some time that winter, George Merritt got sick. Suffering from intense fevers and chills, he was moved to a hospital in North Carolina. On February 7, 1863, he died of “swamp fever” and was buried “from the hospital.”2

What the letter doesn’t tell us is that Adna was only 44 years old when he died. It doesn’t say how his wife and children learned of his death. Knowing he was buried the day he died, we understand that he was in the ground before most people knew he was dead. We see that immediately following his death a group of friends or co-workers carried his body from Charlestown to Hingham by sailboat. We know the news was rushed to Hingham Centre, and that the Fearing Burrs opened their home for an unexpected funeral. We realize that, in a matter of hours, a coffin was acquired, a gravedigger found, and a minister fetched. We are left to imagine the ripples of grief that spread across the villages and towns as friends and family heard the news.

What the letter doesn’t tell us is that Adna was only 44 years old when he died. It doesn’t say how his wife and children learned of his death. Knowing he was buried the day he died, we understand that he was in the ground before most people knew he was dead. We see that immediately following his death a group of friends or co-workers carried his body from Charlestown to Hingham by sailboat. We know the news was rushed to Hingham Centre, and that the Fearing Burrs opened their home for an unexpected funeral. We realize that, in a matter of hours, a coffin was acquired, a gravedigger found, and a minister fetched. We are left to imagine the ripples of grief that spread across the villages and towns as friends and family heard the news.