Dr. Robert Thaxter was born in Hingham on October 21, 1776, only months after the 13 American colonies declared their independence from Great Britain. This was of course a year symbolic of strength, resilience and change, and the same can be said of Dr. Thaxter, who possessed this type of fortitude and a commitment to helping others that one day would claim his life.

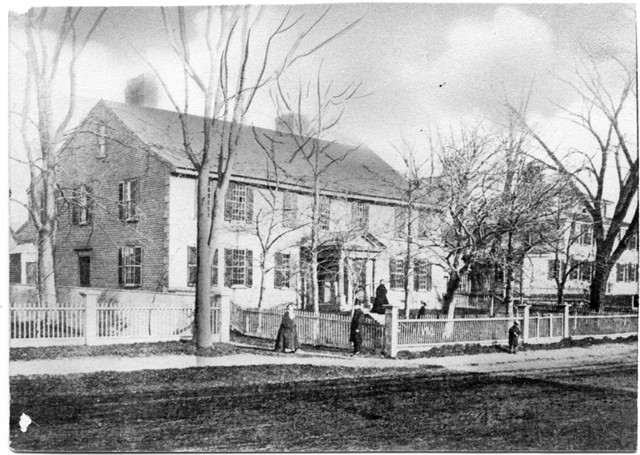

Tranquility Lodge, 137 Main Street, Hingham

Likely born in his grandparents’ house at 21 Lincoln Street (now known as the Hingham Historical Society’s Old Ordinary), Robert Thaxter grew up at 137 Main Street in Hingham, a lovely home once called “Tranquility Lodge,” sitting just down aways on Main Street from Hingham’s 1681 Old Ship Church Meeting House.

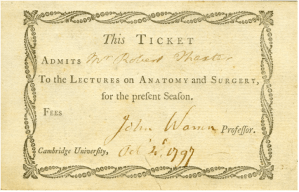

He graduated from Harvard College in 1798 and attended the highly selective private cadaver lectures in Anatomy and Surgery offered by the famous surgeon Dr. John Warren (1753-1815), who would go on to be a founder of Harvard Medical School. Dr. Robert Thaxter’s original admission ticket to Dr. Warren’s class is seen below. Robert soon joined the Massachusetts Medical Society and in 1824 delivered that body’s annual oration, titled A Dissertation on the Excessive Use of Ardent Spirits.

Robert continued a family tradition as a highly respected medical doctor. He was mentored by and practiced with his father, Dr. Thomas Thaxter, in the study of medicine and surgery in Hingham. Dr. Thomas Thaxter was of deep Hingham roots, as “the family of Thaxters were among the early settlers of that town.” (The Boston Medical and Surgical Journal, Vol, XLVI., Wednesday, May 19, 1852. No.16 pg. 309)

Robert continued a family tradition as a highly respected medical doctor. He was mentored by and practiced with his father, Dr. Thomas Thaxter, in the study of medicine and surgery in Hingham. Dr. Thomas Thaxter was of deep Hingham roots, as “the family of Thaxters were among the early settlers of that town.” (The Boston Medical and Surgical Journal, Vol, XLVI., Wednesday, May 19, 1852. No.16 pg. 309)

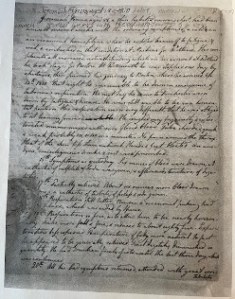

Dr. Robert Thaxter kept detailed records of his patients. His medical diary is a treasure that the Hingham Historical Society holds in its archives. He had a unique writing style and in one journal entry describes the travels of a critically ill man who journeyed from northern Maine for medical care.

This was a demanding trip in the 19th century even for a healthy person let alone one with a critical illness. But Dr. Thaxter was a physician of both the rich and the poor and a healer with an extensive reputation as a doctor both near and far. The doctor’s notes reflect his high level of compassion for this distressed patient. His concise description of the patient’s clinical findings also shows a modernist sensibility in terms of his ability to describe clinical findings with a degree of precision. At that time, treating patients was limited by the lack of today’s medicines such as antibiotics which may have cured this patient. Dr. Thaxter did a remarkable job taking care of patients with the limited pharmacopoeia available at that time. Dr. Thaxter’s 1810 entry regarding his examination of this sick patient is as follows.

This was a demanding trip in the 19th century even for a healthy person let alone one with a critical illness. But Dr. Thaxter was a physician of both the rich and the poor and a healer with an extensive reputation as a doctor both near and far. The doctor’s notes reflect his high level of compassion for this distressed patient. His concise description of the patient’s clinical findings also shows a modernist sensibility in terms of his ability to describe clinical findings with a degree of precision. At that time, treating patients was limited by the lack of today’s medicines such as antibiotics which may have cured this patient. Dr. Thaxter did a remarkable job taking care of patients with the limited pharmacopoeia available at that time. Dr. Thaxter’s 1810 entry regarding his examination of this sick patient is as follows.

Jeremiah Ferino: Jeremiah, 28, a thin habit, (and) narrow chest, had been unwell several weeks with the ordinary symptoms of a cold an occasional haemophysis, when he exhaled himself to fatigue (and) … (and) embarked in that condition at Machias for Portland.

His complaints all increased notwithstanding which on his arrival at Portland he took stage for Boston. At Portsmouth he was stopped one day by epistaxis then … his journey to Boston, where he arrived April 14th, 1810.

That night he was unable to lie down in consequence of laborious respiration. The next day he came to Dorchester worn down by fatigue (and) disease. He was still unable to lie in a horizontal position. His respiration was so very difficult that he was obliged to sit leaning forward. He coughed very frequently (and) expectorated mucous mixed with very (fluid) blood.

To have medicines on hand as a doctor, his father, Dr. Thomas Thaxter was also proprietor of a pharmacy in Hingham, which Robert’s maiden aunt, Abigail Thaxter, ran. (History of the Town of Hingham, 1893; Vol II, page 323; “Native and Resident Physicians” by George Lincoln.) The Thaxter pharmacy would have had a wealth of compounds, elixirs, herbs, and other medicinal items that the young Robert Thaxter could access to treat and cure ailments of that time. Dr. Robert Thaxter’s beautiful wooden medicine chest is also in the collection of the Hingham Historical Society. His medicine chest contains thirteen mold blown glass bottles, many of them with original paper labels. The bottles are labeled with interesting ingredients such as maraschino, strawberry syrup, ginger, parfait amour, rose water, spirit of camphor, orange, oil of cinnamon, oil of cloves, and aromatic elixir. Today, most of these items would be found in our kitchen spice rack rather than our medicine cabinet.

Once trained, Robert Thaxter stayed in Hingham side by side with his father and continued the medical practice. They were both driven and ambitious men but by 1809, Dr. Robert Thaxter needed his independence. He moved his medical practice to Dorchester. Not surprisingly, he was “immediately received into popular confidence which he retained until his death.” (The Boston Medical and Surgical Journal, Vol, XLVI., Wednesday, May 19, 1852. No.16 pg.309). Dr. Thaxter was married to his love of medicine and never took a wife. Once settled in Dorchester, he posted the following advertisement in the July 22, 1809 Columbian Centinel Newspaper:

NOTICE: Doctor Robert Thaxter informs the Inhabitants of Dorchester that he has taken lodgings at the residence of Mr. William Richards, where he will be ready at all times to attend to his profession. He will inoculate with kine Pox, free of expense, all persons who feel themselves unable to pay.

(History of the Town of Hingham, 1893; Vol II, page 324. “Native and Resident Physicians” by George Lincoln.)

At that time, Boston was a homogeneous and in many ways provincial society, with a deeply rooted regard for its protestant English past. Irish immigrants now flooded into Boston hoping for a second chance in life. These Catholic newcomers, though, were seen as a threat to the norms of Boston society. Dr. Thaxter’s decision to relocate his practice to Dorchester was a bold move. He might have damaged his reputation as a doctor by leaving, but he didn’t and still returned to the area to perform surgeries (The Boston Medical and Surgical Journal, Vol, XLVI., Wednesday, May 19, 1852. No.16 pg.309).

Once settled in Dorchester his reputation took off. Dr. Thaxter’s diligence, careful medical observation, and never-ending dedication to the sick expanded his medical practice to neighboring areas. As time went on, he also was drawn to the Irish poor now arriving in Dorchester. “The Irish population gathered more thickly about him . . . . By night and by day, he was at their beck,” (The Boston Medical and Surgical Journal, Vol, XLVI., Wednesday, May 19, 1852. No.16 pg.312)

Dr. Thaxter’s commitment as a doctor to serving the needy, poor, and especially, those from Ireland fleeing the potato famine is commendable—then and now. Those emigrating by what were later called “coffin ships” from Ireland carried poor passengers in steerage where there was a lack of food, plenty of filth and diseases running rampant such as typhus. (As described in a Hingham Historical Society lecture, “The Irish Riviera and Hingham’s Irish 1850-1950,” available for viewing here, typhus and other infectious diseases were killers without our present-day antibiotics.

Dr. Thaxter met his end doing what he believed in. “He fell a martyr to the ship fever (typhus fever), caught in attending an Irish family, just from on board ship.” (Obituary, Boston Daily Evening Transcript 11 Feb 1852). It was said that “Dr. Thaxter never stopped helping the Irish.” (Ibid.) He had a charitably rich and spiritual life to the end. Dr. Thaxter died February 9th, 1852. He was 75 years old. (History of the Town of Hingham, 1893; Vol II, page 324; “Native and Resident Physicians” by George Lincoln.)

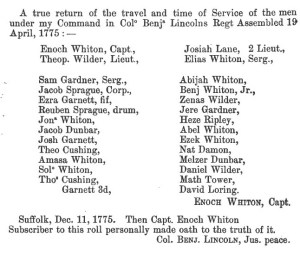

To learn more about the Thaxter family and its place in local and American history, please see our post One if By Land, Two If By Sea on this blog. You might also look at the recent publication, Revolutionary War Patriots of Hingham, by Ellen Miller and Susan Wetzel, Dec 26, 2023, which details the town’s Patriots, including quite a few from the Thaxter family who left their mark in history.

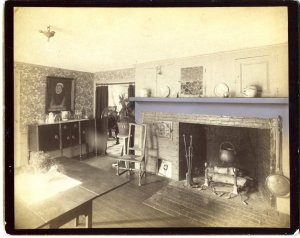

Abigail (Smith) Thaxter

If you are in Hingham, you also may want to visit Dr. Thaxter’s likely birthplace, the Old Ordinary. There you can see a portrait of Dr. Robert Thaxter’s grandmother, Abigail Smith Thaxter, hanging in the parlor.

Dr. Robert Thaxter’s spirit carries on today in public service and health. This tradition of outreach and assistance to those most disadvantaged continues in the Boston area such as the work of the late Dr. Paul Farmer and the continuing work of Partners in Health, and Dr. Jim O’Connell and Boston Health Care for the Homeless, as well as numerous others dedicating their lives to helping those in need.