When John Barker, subject of two prior posts on this blog (“A Soldier Writes Home” and “John Barker at Gaines Mill”), went off to war in 1861, 15-year old Francis H. Lincoln of Hingham was a student at Derby Academy. In two bound volumes, preserved in our archives, he minutely described his primary and secondary education. The Academy’s rules (memorialized in these books) provided that “the writing of compositions be required of the scholars as often as once a fortnight during each term.” Lincoln recorded each of his efforts in these volumes.

Two of Lincoln’s compositions written during his last year at Derby took current events as their subject–South Carolina’s secession from the Union, the election of a distant relation as President, and the coming of war. In February 1861, two months after South Carolina seceded, he penned “A Fable on the Times”:

“Once upon a time” when the people of the United States elected their President, the South or Southern States, the inhabitants of which were mostly Democrats, generally outvoted the Republicans and other parties of the North; but in 1860 at the Democratic conventions, for nominating candidates for the Presidency they were unable to agree, and Republicans outvoted the other parties, and selected Abraham Lincoln of Illinois, President.

Mr. Lincoln being a man opposed to slavery, South Carolina, a miserable little State, tried to rebel against the Union, by seceding and making war, endeavoring to get some other small states to join her, and form what they intended to call the “Southern Confederacy.”

How this will turn out, nobody knows, but probably the Republicans will be masters of the Union.

“Haec fabula docet” that persons must not think that they can be masters of everything, that they must be sometimes willing to give way to others; and it is best to begin these habits in early life, for the child that is permitted to have its own way will grow up like South Carolina creating hatred, and perhaps war. Therefore, O parents, “lead up children in the way they should go;” therefore, O Republicans, do your best; correct South Carolina in her mad course, and “lead it up in the way it should go.”

Inauguration of Abraham Lincoln, March 5, 1861. Photo from Lincoln Collection, Library of Congress

The next months were eventful. Lincoln’s June 1861 composition was titled, “Fort Sumter”:

This fort, which is situated upon an island in the harbor of Charleston, South Carolina; was taken by Secessionists in the spring of 1861, shortly after the inauguration of Abraham Lincoln as President of the United States.

Although much might be said about Fort Sumter, I shall not confine myself to that in particular, but shall write concerning the present rebellion in general.

The Southern or slave-holding states, especially South Carolina, have probably desired to be separated from the Northern for more than twenty years; and until now have not had what they thought could be called a reasonable excuse. Once, I believe, during the administration of Andrew Jackson, they made an attempt at secession, but failed, as they must now.

They have now made the excuse, that Lincoln will interfere with their institutions, and do all in his power, to free their slaves; but this is nonsense; for Lincoln said in a speech before he was elected, “I shall not meddle with their institutions or slaves, but I shall certainly not permit them to extend slavery any farther than it has now gone.”

Persons who had sworn allegiance to the Government and Laws of the United States, have proved traitors, and have done all in their power to destroy the Union; and have done, also, to accomplish this object, the worst thing they could have done for themselves, that is, opened war upon us; and when Major Anderson (who was in command at Fort Sumter) and his handful of men, were nearly starved, opened fire upon him, and shame upon him, a Massachusetts man was the first to fire upon him.

The North should and will have revenge. “The Union must and shall be preserved.” There are still at the South, many who would give all their property to preserve the Union, and such men should be delivered from the hands of those mean and cowardly scamps who are compelling them hither to die or fight for them.

But they will be freed, and their persecutors punished, and if the leaders, viz. Jefferson Davis & Gen. Beauregard and a few others escape with their lives they may congratulate themselves.

They are slaves that fail to speak/ for the fallen and the weak

True freedom is to be earnest to make OTHERS free

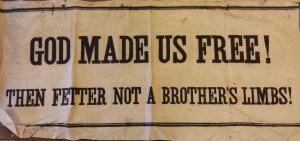

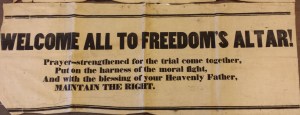

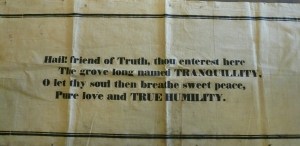

The efforts of the Hingham abolitionists contributed to the larger national abolition movement which would continue to gain traction across the country until the Emancipation Proclamation brought their hard work to fruition. The banners remain an evocative reminder of Hingham’s participation in that important work, and their powerful statements still right true to this day.

The efforts of the Hingham abolitionists contributed to the larger national abolition movement which would continue to gain traction across the country until the Emancipation Proclamation brought their hard work to fruition. The banners remain an evocative reminder of Hingham’s participation in that important work, and their powerful statements still right true to this day.