“To All Christian People to whome this present instrument shall come Greeting,” this deed in our archives opens magisterially. The date at the bottom is equally impressive: July 4, 1690, “Anno Regni & Regina Guilielmi & Maria Secundi” (in the second year of the reign of King William and Queen Mary). The deed is executed by William Stoughton, “of Dorchester in the Colony of the Massachusetts Bay in New England,” and conveys several parcels of land in the vicinity of Broad Cove to Thomas Thaxter “of Hingham in the Colony aforesaid, yeoman.” Stoughton is acting on behalf of “the Governor and Company established & residing in the Kingdome of England for the propagation of the Gospel to the Indians in New England &c.”

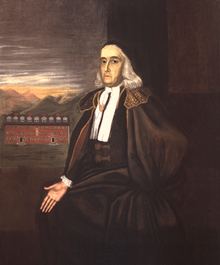

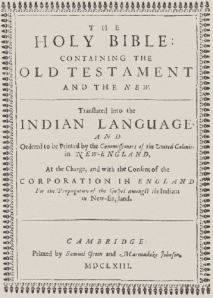

In addition to his service as a judge during the Salem witch trials (see our prior post about this document, “William Stoughton’s Seal”), and later service as first Chief Justice of Massachusetts’ Supreme Judicial Court, Stoughton was Lieutenant Governor of the Colony in the 1680’s and early 1690’s. Among his many other public positions was Commissioner, and later Treasurer to the Commissioners, of the Company for the Propagation of the Gospel to the Indians in New England and the Parts Adjacent in America, a company chartered by Parliament in 1649 to support the conversion of New England’s native people. The Company originally made investments in England and sent the income to the colonies, to be used to support conversion efforts, including John Eliot’s 1663 translation of the Old Testament into the Massachusett language, the creation of settlements for the so-called “Praying Indians” (including present-day Stoughton, Mass.), and other missionary activities such as the creation of a short-lived “Indian College” at Harvard College. (These efforts may be familiar to readers of the recent historical novel Caleb’s Crossing, by Geraldine Brooks.)

Poor returns on investments in England (including losses owing to the Great Fire in London) led the New England Company to start to send capital for investment in the colonies. The task of finding suitable investments fell to Stoughton. Two such investments, made in 1683, were loans of £50 each to Simon and Joshua Hobart of Hingham, sons of Captain Joshua Hobart, nephews of the Rev. Peter Hobart, and both identified as “mariners.” The loans were secured by real estate in Hingham and, according to the legal structure of the day, evidenced by deeds conveying the parcels to Stoughton, upon the condition that if the greater sum of £66 was repaid four years hence, in 1687, the sale would be null and void.

Poor returns on investments in England (including losses owing to the Great Fire in London) led the New England Company to start to send capital for investment in the colonies. The task of finding suitable investments fell to Stoughton. Two such investments, made in 1683, were loans of £50 each to Simon and Joshua Hobart of Hingham, sons of Captain Joshua Hobart, nephews of the Rev. Peter Hobart, and both identified as “mariners.” The loans were secured by real estate in Hingham and, according to the legal structure of the day, evidenced by deeds conveying the parcels to Stoughton, upon the condition that if the greater sum of £66 was repaid four years hence, in 1687, the sale would be null and void.

It is not clear what happened to the younger Joshua Hobart’s land but, on July 4, 1690, Stoughton sold the land he had “purchased” from Simon Hobart to Thomas Thaxter, for the inappropriately small sum of £4. In all likelihood, this sale to Thaxter was part of some larger transaction, of which we know nothing.

How did Stoughton come to loan the New England Company’s funds to the Hobart brothers? Stoughton had reason to be familiar with Hingham real estate in the early 1680’s. In 1681, Hingham needed a new church, but a dispute arose about where to locate it. The decision where to build what would become Old Ship Church was elevated to the General Court, which appointed an oversight committee, on which Stoughton served. The Committee determined that the Church would be located on property purchased from Captain Joshua Hobart, adjacent to the parcels involved in the New England Company financing two years later.

How did Stoughton come to loan the New England Company’s funds to the Hobart brothers? Stoughton had reason to be familiar with Hingham real estate in the early 1680’s. In 1681, Hingham needed a new church, but a dispute arose about where to locate it. The decision where to build what would become Old Ship Church was elevated to the General Court, which appointed an oversight committee, on which Stoughton served. The Committee determined that the Church would be located on property purchased from Captain Joshua Hobart, adjacent to the parcels involved in the New England Company financing two years later.

From the Salem witch trials to the Praying Indians and back to Old Ship Church, this one old deed shows just what a small world 17th century Massachusetts Bay was.