I had no idea when I retired in March 2015 that so much of my early retirement would involve projects tied to history. These projects culminated in the Hingham Historical Society‘s Custom Google Map Project, which I have shepherded for the past year. As the opening of the Visitor Center at the Historical Society’s newly renovated Old Derby Academy approaches, it is exciting to unveil our work. The new Hingham Heritage Map is a custom Google map with a series of topical overlays on which locations of local historical significance are geo-located and described.

Not sure what that means? Just click in the upper left hand corner to see the “legend,” or list of overlays, and in the upper right hand corner to enlarge the map:

Select one of the themed layers using the map “legend” on the left, and the Google map will populate with icons representing sites of interest. Click on one and scroll down to read more about its history and in some cases, see historic and contemporary photos. Note: Many historic structures on this map are private homes today, but exteriors can be viewed as you walk, bike, or drive along.

Eileen McIntyre with veterans Norm Grossman and Syd Rosenburg (Barry Chin photo for Boston Globe)

Over the past two years, I was pleased to make connections with fellow history-minded Hinghamites whose help and encouragement made the project possible. In late 2015, I met with Andy Hoey, Director of Social Studies in the Hingham Public Schools, to explore ways I could put my experience with a new StoryCorps smartphone app to use, capturing oral histories. I’d originally thought I might work with some students to encourage their use of the app. Andy suggested that I consider capturing stories of local military veterans and introduced me to Keith Jermyn, Hingham’s Director of Veterans’ Services. I kept in touch with Andy as I interviewed veterans in town over the succeeding months to come. The initiative was covered in a Globe South story that ran with their Veterans Day coverage last year. While we did not realize it when we connected about StoryCorps, both Andy and Keith would later prove helpful in the map project.

Detail from W.A. Dwiggins map, “The Old Place Names,” 1935

In March of 2016, I met with Suzanne Buchanan, then Executive Director at the Hingham Historical Society, and others to explore a potential way-finding project for the planned opening of the Visitor Center at the Hingham Heritage Museum. Over the next several weeks, I researched an earlier signage project explored by the Hingham Downtown Association. My findings suggested that adding more signs to point visitors to Historic Downtown Hingham, and the new Museum, would be challenging. I also realized that for most of us these days, physical way-finding signs are not a major navigation tool. As I pondered this, an unrelated event sparked an idea.

In the spring of 2016 I attended my 45th college reunion and was impressed by a custom Google map the Boston College alumni office had created to guide attendees to the events held on two campuses. I wondered if we could design such a map as an easy-to-access resource to the Hingham history all around us–so I contacted the BC alumni office to find out how the map had been created. The Associate Director, Strategic Marketing and Writing, of the Office of University Advancement, Stacy Chansky, was very helpful, sending me online resources. Wow, I thought. Maybe some local students could be enlisted to help me with create a custom Google map to showcase Hingham history that would launch when the new Hingham Heritage Museum opened.

I shared my idea with Suzanne and, based on her enthusiasm for the concept, I reached out to Andy Hoey to see if any Hingham High School students could be enlisted when school resumed the following September. Andy came through for me, not only identifying two interested seniors, but also gaining approval for them to receive course credit for the hours they spent on the project. Seniors Eliza Cohen and Collin Bonnell and I agreed on a multi-themed approach to mapping the history of our Town. Our objective would be not only to pinpoint locations but also to include text and photographs.

First Universalist Church and Society, now a private home on North Street.

Both students had themes they wanted to research. Eliza set off to document the Town’s historic meeting houses, places of worship, and cemeteries, while Collin dove into Hingham’s rich military history across the centuries. (I contacted Keith Jermyn about Collin’s work and he contributed by giving Collin material on the many military monuments around town.) Later, Collin also would help me research Hingham’s farming history.

Banner from Hingham’s historic 1844 abolitionist event at Tranquility Grove (Burns Memorial Park today).

Other topics I took on were bucket-making and other early industry in town and the history of Tuttleville, a 19th-century freed black community in Hingham. This latter topic would later expand to include Hingham’s historic relationship to our nation’s abolition movement. Each research topic would become a layer of the custom Google map. And I made sure that the Hingham Heritage Museum would be represented on each map layer, through a reference to archival materials or artifacts related to the theme for that layer of the map. (I’ve learned much along the way about the rich resource our new museum will be for all kinds of research.)

As the project got underway last fall, the Society’s registrar, Michael Achille, helped us find information and photographs from the Society’s archives and the Public Library’s history collections. Michael has been invaluable as both an expert resource and a cheerleader throughout this project. He is now working with Andy Hoey on an Historical Society-sponsored internship for Hingham High School students starting next fall. Assignments for the students are expected to include future enhancements to the custom Google map we have created for the Heritage Museum.

For a project with the scope of ours, it was best to begin by populating a shared database. We made Google sheets the home for all of the data we began collecting beginning last September. Later in the fall, one of my contacts from the StoryCorps project, Hingham-based journalist Johanna Seltz Seelen, put me in touch with Yael Bessoud, a university-level history student with good technology skills–and her future son-in-law. Yael joined our team early this year, first researching photographs at the library and in the Society archives and then referencing the Hingham Comprehensive Community Inventory of Historic, Architectural and Archeological Assets to populate the database with content for additional Google map layers, including ones documenting the more than one hundred pre-1800 homes and other structures still standing in Hingham. Later, Yael was instrumental in transferring the information we had put into our database onto a Google map.

Everyone involved in this project is excited that, less than a year from the project’s inception, we are launching what is now an eight-layer custom Google map documenting so many aspects of the Town’s history. I want to give special shout-outs to Eliza Cohen, who is beginning her college studies at the Shanghai, China, campus of New York University; Collin Bonnell, who is off to college at Fordham University in New York City, and Yael Bessoud, who, with an Associate Degree in History from Quincy College completed, is now continuing his studies toward a B.A. in Education at Framingham State University.

The map project is ongoing. I appreciate the recent assistance of Geri Duff, who found digital images for many of the historic homes on the Google map and house histories compiled by Historical society volunteers over many years of Hingham Historical House Tours. With these, I have been able to enrich the descriptions for many sites.

Other resources of value to the project have included: the entries on this blog, which document many of the archival resources that we have tied into map descriptions; Martha Reardon Bewick’s well-researched Lincoln Day address this year, which filled in much detail about the abolitionist gathering at Hingham’s Tranquility Grove (a site on one of the map layers); photos and stories provided by Town Historian Alexander Macmillan; and valuable clues about Hingham’s extensive dairy farm history provided by Peter Hersey, based on the labels from his historic milk bottle collection.

Any project worth doing “takes a village” . . . or in this case, a Town.

We don’t have many interior views this nice of the old Hingham shops. On the shelves of E. Wilder and Son Grocery Store (at 613 Main St., now the

We don’t have many interior views this nice of the old Hingham shops. On the shelves of E. Wilder and Son Grocery Store (at 613 Main St., now the

His son,

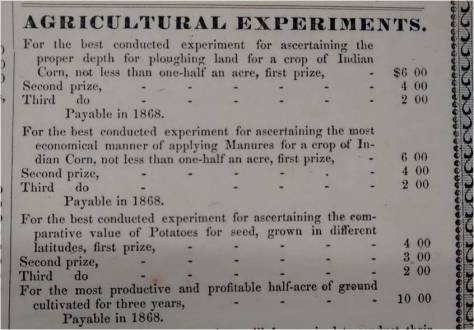

His son,  The Hingham Agricultural and Horticultural Society, founded in 1869, was also comprised of local men and women, many of whom were involved in industry, trade, and commerce. (Here, they pose for a formal portrait in front of Hingham’s Agricultural Hall in the late 1880s or early 1890s.) As a society, they were earnestly dedicated to scientific farming, that is, using the progressive values of the 19th century and the power of new knowledge and industrial technology to “improve” agriculture along “modern” lines. At the agricultural fair each fall, prizes offered in different categories attracted many entrants. One could win a medal or ribbon—and an accompanying cash prize–for anything from crops and livestock to flowers and preserves.

The Hingham Agricultural and Horticultural Society, founded in 1869, was also comprised of local men and women, many of whom were involved in industry, trade, and commerce. (Here, they pose for a formal portrait in front of Hingham’s Agricultural Hall in the late 1880s or early 1890s.) As a society, they were earnestly dedicated to scientific farming, that is, using the progressive values of the 19th century and the power of new knowledge and industrial technology to “improve” agriculture along “modern” lines. At the agricultural fair each fall, prizes offered in different categories attracted many entrants. One could win a medal or ribbon—and an accompanying cash prize–for anything from crops and livestock to flowers and preserves.

A new exhibit opened today at our 1688

A new exhibit opened today at our 1688

After his trip west Sprague returned briefly to the South Shore, working as a clerk in a Nantasket Beach hotel until, the following year, he started to work as an illustrator for prominent American botanist

After his trip west Sprague returned briefly to the South Shore, working as a clerk in a Nantasket Beach hotel until, the following year, he started to work as an illustrator for prominent American botanist