When a local developer purchased the Rev. Ebenezer Gay (1696-1787) house at 89 North Street, local historian John P. Richardson participated in some pre-construction historical investigations. These painted panels from the Gay house, later installed in the 1690 Old Fort House which Mr. Richardson owned and occupied, are now part of the John P. Richardson Collection at the Hingham Historical Society.

Wall Fragment from the Ebenezer Gay House. John P. Richardson Collection, Hingham Historical Society.

The first wall fragment is made of a plaster and lath surface attached to heavy vertical boards, which are in turn attached to two more modern boards horizontally laid. The decorative side is painted a dirty off-white base with a meandering vine ad flower motif that originates out of a basket or planter decorated in a cross hatch pattern with dots in each diamond of the crosshatch. The basket rests on a hilly green stylized landscape. The vine bears large, stylized acanthus-type leaves and flowers of varying shapes in red and blue. Five hand-cut nails protrude from the wall—two at the far left, one at the top center, one at the upper right, one at mid-right.

Wall Fragment from the Ebenezer Gay House. John P. Richardson Collection, Hingham Historical Society.

The second decoratively painted wall fragment consists of two layers of plaster and lath encasing two heavy vertical boards. The plaster side is painted with at least 2 layers of paint, the topmost having been added by a 20th century Gay family member seeking to restore the design. The original background was green, while the background of the current surface layer is a dirty tan color.

A meandering vine motif climbs the panel, with the vine bearing red tulip-shaped blue lily-shaped flowers. At right is a narrow border set off by a dark brown line. Within the border the flower and vine motif repeats in a narrower scale. To the right of the border is an unfinished area of white plaster with two maroon colored squares of paint laid out in a windowpane pattern.

In his book, The Benevolent Deity: Ebenezer Gay and the Rise of Rational Religion in New England, author Robert J. Wilson III described the Gay house at it looked during the years that Ebenezer lived there with his wife, Jerusha (Bradford) Gay and their ten children:

The house was a 2-1/2 story, rectangular, pitched-roof affair, somewhat large for the period, but not ostentatiously so. Though it was painted a rather austere blue-gray on the outside, the interior was lively and colorful. Someone (Jerusha?) adorned the cream colored walls of the family sitting room with a free hand vine design, very like eighteenth-century crewelwork. The woodwork, fireplace wall, and the wainscott (added later) were all painted a light green. The whole effect suggested that nature’s god in all his vibrancy was very much alive in the Gay house.

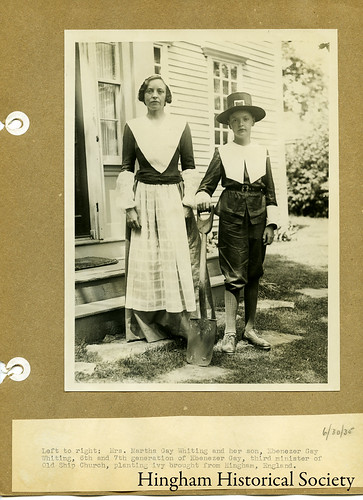

Hingham pulled out all the stops in preparation for its 300th anniversary celebration. Twelve hundred of the Town’s residents participated in a three-plus hour historical pageant, which was performed before 2,000 attendees on the evenings of June 27, 28, and 29, 1935. In the midst of the Great Depression, the Town appropriated an astonishing $14,000 for its tercentenary observance, which was written and directed by

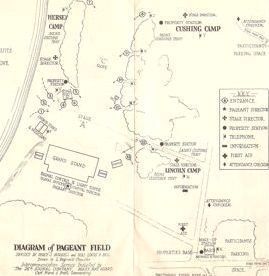

Hingham pulled out all the stops in preparation for its 300th anniversary celebration. Twelve hundred of the Town’s residents participated in a three-plus hour historical pageant, which was performed before 2,000 attendees on the evenings of June 27, 28, and 29, 1935. In the midst of the Great Depression, the Town appropriated an astonishing $14,000 for its tercentenary observance, which was written and directed by  “The Pageant of Hingham” was performed on a sprawling outdoor set at what was then called

“The Pageant of Hingham” was performed on a sprawling outdoor set at what was then called

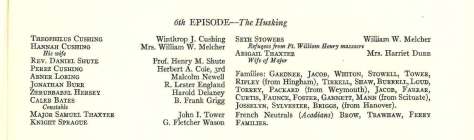

Young Newell and Herbert Cole, another Hingham boy also cast as an 18th century Hingham boy (Perez Cushing, 1746-1794), called out the names of the guests arriving at the Cushing farm. An example of their lines, taken from the Pageant Program:

Young Newell and Herbert Cole, another Hingham boy also cast as an 18th century Hingham boy (Perez Cushing, 1746-1794), called out the names of the guests arriving at the Cushing farm. An example of their lines, taken from the Pageant Program:

These seven Hingham boys posed with three bicycles are witnessing the birth of modern cycling. Behind them are two older bicycles—so-called “high wheelers” or “penny farthings” (the latter nickname descriptive of the relative sizes of the two wheels). High-wheelers originated in England and became popular in the United States in the early 1880s. As this photo lets us see clearly, these early bicycles had a “direct drive” mechanism, that is, the pedals attach directly to the wheel, so that the cyclist’s motion turns the wheel directly. Enlarging the front wheel, therefore, was the only way to make the bicycles go faster–and this is what happened. Front wheels often five feet in diameter, with the cyclist perched directly over the wheel, meant an increased risk of the cyclist pitching headfirst from the front of his bike. Cycling in the era of the high wheelers was a sport for athletic young men.

These seven Hingham boys posed with three bicycles are witnessing the birth of modern cycling. Behind them are two older bicycles—so-called “high wheelers” or “penny farthings” (the latter nickname descriptive of the relative sizes of the two wheels). High-wheelers originated in England and became popular in the United States in the early 1880s. As this photo lets us see clearly, these early bicycles had a “direct drive” mechanism, that is, the pedals attach directly to the wheel, so that the cyclist’s motion turns the wheel directly. Enlarging the front wheel, therefore, was the only way to make the bicycles go faster–and this is what happened. Front wheels often five feet in diameter, with the cyclist perched directly over the wheel, meant an increased risk of the cyclist pitching headfirst from the front of his bike. Cycling in the era of the high wheelers was a sport for athletic young men.