When we think of tourism in Massachusetts, examples such as Hull’s Nantasket Beach, Cape Cod’s Provincetown, or Martha’s Vineyard’s Edgartown immediately come to mind. Perhaps surprising to some, Hingham held a role as a tourist destination, possessing three resort hotels throughout the 19th century.

First built in 1770, the Union Hotel was constructed where the Hingham Post Office stands today. In the early 19thcentury, it was renamed the Drew Hotel and then later the Cushing House and underwent various renovations before it was torn down in 1949.

Next, the Old Colony House was built in 1832 on top of Old Colony Hill, close to what is now Summer Street, with grounds extending to Martin’s Well. Founded by the Boston and Hingham Steamship Company, it burned down in October of 1872.

Thirdly, in 1871 the Rose Standish House was constructed in what is now Crow Point. The hotel was part of Samuel Downer’s Victorian-era amusement park, Melville Garden, until the park was dismantled in 1896.

What were some of the factors contributing to Hingham’s rise in tourism?

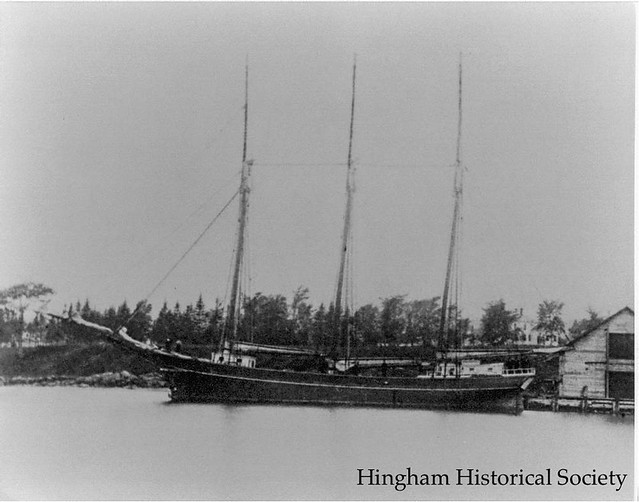

While Hingham could be accessed by horse drawn carriage, the development of steamships and railroads during the 1800s was important to connecting small, rural towns like Hingham to Boston’s wealthy citizens, and later the general public, in order to grant quick access to the pleasures they had to offer.

Furthermore, with the increase in urbanization due to the Industrial Revolution, towns such as Hingham became places of escape from the city’s hustle and bustle. As cities grew, doctors and scholars began to associate the city with not only various physical diseases but also mental maladies. While sea bathing and the sea air were thought to possess healing properties, it was also considered salubrious to take a respite from the city itself. An excerpt from the research magazine Scientific American, published in 1871, discussed the medical benefits of a seaside visit for people suffering from a variety of ailments: from anxious businessmen, to people living in crowded towns, or to people recovering from illness or injury. The author stated

To these people it is not the sea air alone, nor yet change of air; but it is change of scene and habit, with freedom from the anxieties and cares of study or business, the giddy rounds of pleasure, the monotony of every-day life, or the sick room and convalescent chamber, which produce such extraordinary beneficial effects . . . .

With the development of a middle class during this time, more people could afford the time and money to engage in leisure activities and embark on day trips to Boston’s surrounding towns. From the naturalistic scenery of World’s End surrounding the Old Colony House to the dancing and boating at the Rose Standish House and Melville Garden, the escapist nature of Hingham’s seaside resorts provided urbanites a sojourn away from the city.

American, regardless of ethnicity, and Eleanor was thrilled to discover that the Hingham High School football squad that year had players whose families had come from eight different parts of the world and that Hingham was home to Dutch and Polish farmers, Italian shoe makers, and a German harness maker, amongst many others. In 1942 Hingham had a population of 8,000. It still had 50 farms—but it also had a commuter train., and much of its population now travelled to work in Boston. There were, of course, schools, churches of all kinds, and a public library with 28,000 volumes. The Loring Hall movie theater would be showing Citizen Kane the following week.

American, regardless of ethnicity, and Eleanor was thrilled to discover that the Hingham High School football squad that year had players whose families had come from eight different parts of the world and that Hingham was home to Dutch and Polish farmers, Italian shoe makers, and a German harness maker, amongst many others. In 1942 Hingham had a population of 8,000. It still had 50 farms—but it also had a commuter train., and much of its population now travelled to work in Boston. There were, of course, schools, churches of all kinds, and a public library with 28,000 volumes. The Loring Hall movie theater would be showing Citizen Kane the following week.

Back in 1946 there was a bit of a housing shortage. Hingham dentist Ross Vroom bought a two-story Garrison colonial house on Gallops Island and had it placed on a barge and floated over to World’s End. He had a cellar dug at 22 Seal Cove Road, and the house still sits there today.

Back in 1946 there was a bit of a housing shortage. Hingham dentist Ross Vroom bought a two-story Garrison colonial house on Gallops Island and had it placed on a barge and floated over to World’s End. He had a cellar dug at 22 Seal Cove Road, and the house still sits there today.

On September 18, 1933, under the headline, “Railroad Tracks Washed Out During Storm Last Sunday,” the

On September 18, 1933, under the headline, “Railroad Tracks Washed Out During Storm Last Sunday,” the  The storm that took out the railroad embankment is not as locally famous as the

The storm that took out the railroad embankment is not as locally famous as the

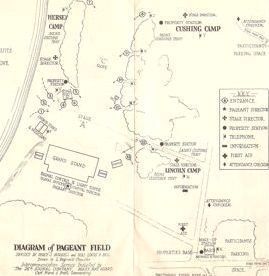

Hingham pulled out all the stops in preparation for its 300th anniversary celebration. Twelve hundred of the Town’s residents participated in a three-plus hour historical pageant, which was performed before 2,000 attendees on the evenings of June 27, 28, and 29, 1935. In the midst of the Great Depression, the Town appropriated an astonishing $14,000 for its tercentenary observance, which was written and directed by

Hingham pulled out all the stops in preparation for its 300th anniversary celebration. Twelve hundred of the Town’s residents participated in a three-plus hour historical pageant, which was performed before 2,000 attendees on the evenings of June 27, 28, and 29, 1935. In the midst of the Great Depression, the Town appropriated an astonishing $14,000 for its tercentenary observance, which was written and directed by  “The Pageant of Hingham” was performed on a sprawling outdoor set at what was then called

“The Pageant of Hingham” was performed on a sprawling outdoor set at what was then called

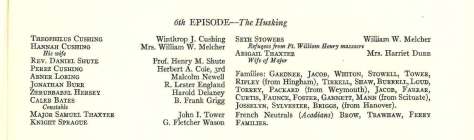

Young Newell and Herbert Cole, another Hingham boy also cast as an 18th century Hingham boy (Perez Cushing, 1746-1794), called out the names of the guests arriving at the Cushing farm. An example of their lines, taken from the Pageant Program:

Young Newell and Herbert Cole, another Hingham boy also cast as an 18th century Hingham boy (Perez Cushing, 1746-1794), called out the names of the guests arriving at the Cushing farm. An example of their lines, taken from the Pageant Program:

These seven Hingham boys posed with three bicycles are witnessing the birth of modern cycling. Behind them are two older bicycles—so-called “high wheelers” or “penny farthings” (the latter nickname descriptive of the relative sizes of the two wheels). High-wheelers originated in England and became popular in the United States in the early 1880s. As this photo lets us see clearly, these early bicycles had a “direct drive” mechanism, that is, the pedals attach directly to the wheel, so that the cyclist’s motion turns the wheel directly. Enlarging the front wheel, therefore, was the only way to make the bicycles go faster–and this is what happened. Front wheels often five feet in diameter, with the cyclist perched directly over the wheel, meant an increased risk of the cyclist pitching headfirst from the front of his bike. Cycling in the era of the high wheelers was a sport for athletic young men.

These seven Hingham boys posed with three bicycles are witnessing the birth of modern cycling. Behind them are two older bicycles—so-called “high wheelers” or “penny farthings” (the latter nickname descriptive of the relative sizes of the two wheels). High-wheelers originated in England and became popular in the United States in the early 1880s. As this photo lets us see clearly, these early bicycles had a “direct drive” mechanism, that is, the pedals attach directly to the wheel, so that the cyclist’s motion turns the wheel directly. Enlarging the front wheel, therefore, was the only way to make the bicycles go faster–and this is what happened. Front wheels often five feet in diameter, with the cyclist perched directly over the wheel, meant an increased risk of the cyclist pitching headfirst from the front of his bike. Cycling in the era of the high wheelers was a sport for athletic young men.