“Raising the liberty pole,” 1776 / painted by F.A. Chapman ; engraved by John C. McRae, N.Y. (Library of Congress)

1774 was a big year for young Samuel Gardner of South Hingham. Over the course of that year, he made five short notations in what had once been his father’s diary: that he was married on January 6; that he commenced “keeping house” on April 27; that his father, Samuel Gardner, Sr., died on November 5; and that his first child, also named Samuel, was born the following day, November 6. The fifth entry, made on October 16, 1774, was, “Liberty pool [sic] raised.” To have merited an entry along with the other four milestones means this, too, was an important event in Samuel’s life.

It has long been reported that a liberty pole was raised in South Hingham. The hill running up Main Street from Glad Tidings Plan to the vicinity of what is now South School was called Liberty Pole Hill in the 19th century, and the name was adopted for a residential subdivision, bounded by Main Street, Cushing Street, and Old County Road, that was constructed in the 1950s and 1960s. But until we located a transcription of Samuel Gardner’s diary in the papers of local historical Julian Loring, we had no written confirmation of or information about Hingham’s liberty pole.

Liberty Pole in the Fields (New York). 1770 cartoon engraved by P. E. du Simitiere. (Library Company of Philadelphia)

What is a liberty pole anyway? Liberty poles erected in colonial towns in the years running up to the American Revolution were symbols of dissent from Great Britain. They were typically tall wooden masts or poles with a red flag or cap on top and often served as the sites of meetings or demonstrations. The reference was classical, recalling stories of a pole topped with a freedman’s cap erected after Julius Caesar’s assassination as a symbol of the Romans’ freedom tyranny. (Boston initially had a Liberty Tree, where in 1765 the Sons of Liberty hanged Andrew Oliver in effigy to protest the Stamp Act, though after British soldiers chopped it down during their occupation of Boston, it was replaced with a liberty pole.)

Liberty poles were raised across New England in the 1760s and 1770s, sometimes in protest (for instance, of the Stamp Act or the Boston Port Act) and sometimes in celebration (for instance, the Stamp Act’s repeal or the opening of the First Continental Congress).

The timing of Hingham’s liberty pole–raised on October 16, 1774–is no surprise. In May 1774, Parliament enacted the Boston Port Act, closing Boston Harbor, and other of the so-called Intolerable Acts as retribution for the Boston Tea Party. Boston’s Town Meeting issued a call for a trade embargo against Great Britain and by mid-summer 1774, Hingham’s Town Meeting had formed a committee to draft a non-importation covenant, or agreement in solidarity with Boston to boycott goods from Great Britain and the West Indies. On August 17, Town Meeting approved the draft covenant but stayed its execution pending action by the First Continental Congress, which had convened on September 5. (By late October, Town Meeting had received and adopted the articles of the Continental Association, a non-importation, non-exportation, and non-consumption agreement against British merchants and goods, in the hopes that economic pressure might encourage Parliament to address colonial grievances.)

On September 21, 1774, the Town heard a report of the Suffolk County Committees of Correspondence and voted its agreement with that body’s resolves, later called the “Suffolk Resolves.” These included boycotting British goods, defying the Intolerable Acts, refusing to pay taxes, and urging the towns to raise and train militias of their own people. Consistent with those resolves, at the same meeting, Hingham voted to recommend “to the officers of the Militia to assemble their men once in the week and Instruct them in the art of War and the Men be provided with Arms and Ammunition According to Law.”

Enoch Whiton House, 1083 Main Street (Hingham Historical Society)

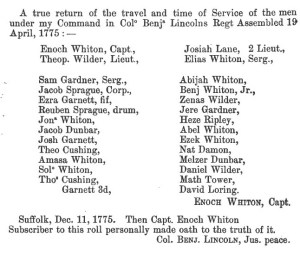

Hingham had several militia companies, roughly organized by geography. Samuel Gardner belonged to the company under the command of Captain Enoch Whiton, a neighbor of his on Liberty Plain. (Captain Whiton’s house still stands at 1083 Main Street; as do those of Samuel Gardner, Sr., and Jr., at 1035 and 1006 Main Street, respectively. It is remembered that Captain Whiton’s company trained in the vicinity of what is now the Marchesiani Farmlands at 1030 Main Street–right across the road from the home of Samuel Gardner, Sr.

The militia men were undoubtedly instrumental in the raising of a liberty pole not far north of their training grounds on October 16, 1774. Their revolutionary activity was only beginning; Captain Whiton’s company mustered and marched on April 19, 1775, when word of Lexington arrived in Hingham.

History of the Town of Hingham, vol. I, pt. 2 (1893)

Great post, Paula, and thanks for investing the time in exploring those materials and finding this evidence at last!

Great story! – an interesting and engaging Hingham history narrative backed by impressive research – and an answer to a question that I’m sure many have asked over the years. Well done and thank you.